Easy configuration management with Puppet

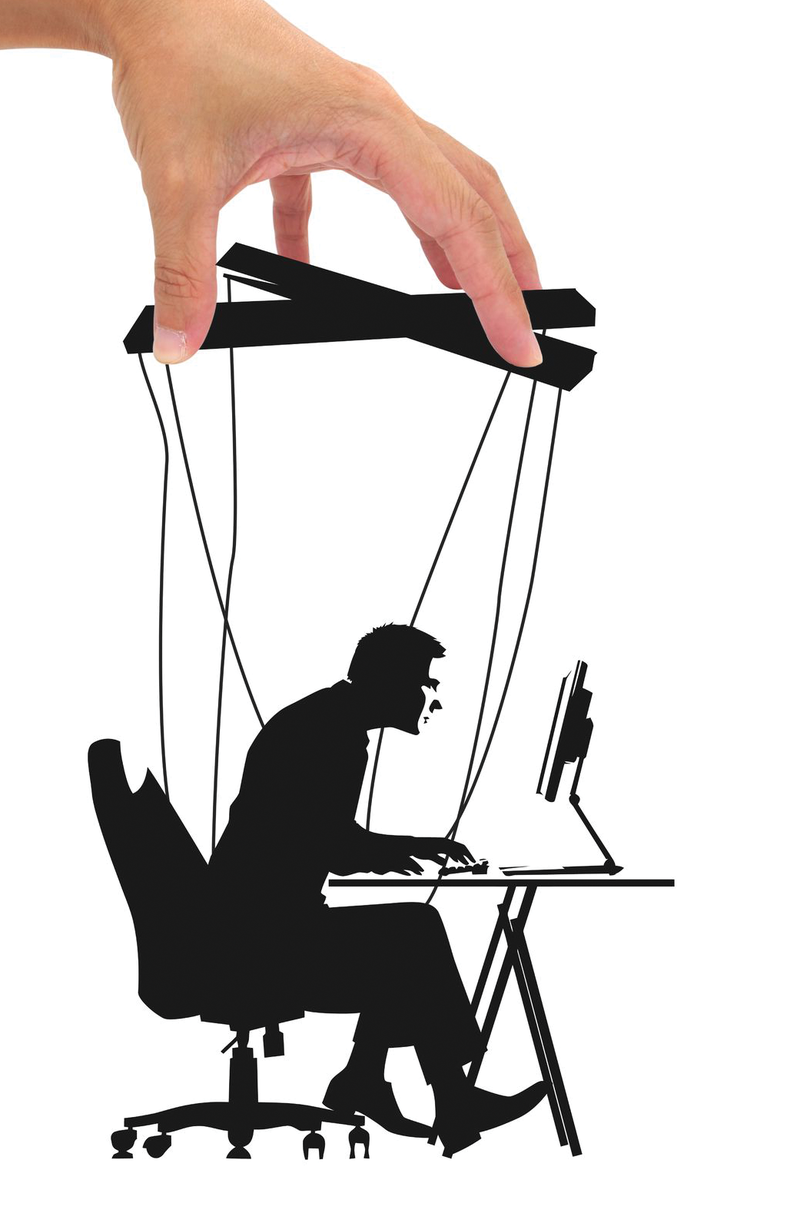

Holding the Strings

Although the configuration management craze is all over the startup world, many computers in this world are not managed in any way other than by very careful sys admins. I have nothing against them – I am glad they're careful – but I'm not, so I need to cheat: I need config management.

Config management sets up servers. It installs stuff, configures it, and makes sure it is working as you requested. The important word is: you. It sets it up as you requested.

Many admins have learned how to configure a server by installing things manually, so automating the configuration steps can lead to uncertainty and scare a few people away. Puppet takes a little time to set up, but I found that once I understood what it was doing, I felt much more able to trust it – even on legacy servers. In this article, I'll present a really simple and fast guide to getting stuff done with Puppet. Once you've worked through this, you'll be able to install and configure most of the major packages out there. It's really very simple.

A Really Fast Intro to Puppet

A lot of admins are using Puppet for increasingly complex systems. The technology has picked up pace in the past year, but for those of us who have either used it a little or not at all, Puppet requires a heap of learning.

In this whirlwind tour, I want to convince you that you should start using Puppet to manage everything, right now.

This is a tour of the terminology and a high-level description of what Puppet does. Instead of treating this as a fresh installation that is going to run a really complex server, I'll take you through installing Puppet locally and using it to control just a few things. Puppet is a really strong tool and can do great things, but until you trust it, you'll treat it with hesitation.

Configuring a server is largely about writing text to files, and this is one of the many things Puppet can do for you. Puppet takes a description of what should be there, compares it with what is there, and changes it to match. For example, configuring an Apache site might require the existence of the file /etc/apache2/sites-enabled/<my-site>.conf, or you might want to make sure a module is configured as you desire: /etc/apache2/conf.d/<some-module>.conf.

In both cases, all that's required is that file exists and the content is as you want it. Would that be enough to run your site? Probably not, because for this command to work, you'll need to install Apache plus maybe a couple of modules. You also need the document root to exist.

A more complete list of what you need to get your site working is:

- Apache

- Some modules

- A couple of config files

- A file in the document root

Puppet gives you building blocks to set all this up.

Install Puppet

Start by installing the latest version of Puppet. Not all versions have the same options, and you don't want to spend your time translating between the options in different versions, so get the latest if you can. I'm only covering the latest version here, which, at the time of writing, is 2.7.x. Using Ubuntu, you can run the following

do-release-update apt-get update apt-get install puppet

to upgrade your server (if desired) and install Puppet. To make sure you have the latest version of Puppet installed, run:

$ puppet --version 2.7.1

This tour focuses on the Puppet command-line tool because I want to make sure you can see the link between what's in the Puppet manifest files and what Puppet does to the server. Understanding this relationship makes working with Puppet on the small and large scale make sense, and it makes Puppet considerably less terrifying.

Create the Puppet Manifest File

To begin, I'll start with a very simple Puppet manifest file. Puppet files are named .pp. The syntax is very simple, looking a bit like JSON, but it is worth noting that a lot of Puppet modules make use of Ruby (including .erb files) and other scripting tools to add more cleverness. The Puppet cli tool runs the .pp files, so when you want to apply a Puppet manifest file to your server, apply it so that, if you create an empty file and run the command

puppet apply <myfile>.pp

Puppet will successfully do absolutely nothing. If you put the following line into the file:

notice("Let's build a server!")

and run it, Puppet says:

$ puppet apply <myfile>.pp notice: Scope(Class[main]): Let's build a server! notice: Finished catalog run in 0.01 seconds

Next, create a simple and largely useless file in the same script, drop the file into a home directory, change the manifest file to

file { "/home/dan/hello.md":

ensure => "present",

mode => '0664'

}

and run:

$ puppet apply <myfile>.pp notice: /Stage[main]//File[/home/dan/ hello.md]/ensure: created notice: Finished catalog run in 0.02 seconds

Now, when you take a look, you'll see that /home/dan/hello.md exists.

Using this technique alone, you can now litter the server with all the files you need, but still keep the best settings in one place: in your Puppet project.

This method is hugely useful for deploying to new servers and tracking changes. Say, for example, you run some experiments and find that changing the memory limits on Apache, along with max children improves performance. Instead of remembering this, you would put it in your Puppet files and ensure that your config files are the ones that are in use.

Update the Message of the Day

For the next project, I will begin with the following structure:

./files/ ./manifests/ ./manifests/init.pp

With the project structure created, I can move a simple file declaration into the init.pp file (Listing 1).

Listing 1: File Declaration

01 $ cat ./manifests/init.pp:

02 package { "update-motd":

03 ensure => installed

04 }

05 file { "/etc/update-motd.d/10-mymotd":

06 ensure => "present",

07 source => "puppet:///modules/mypuppets/misc/10-mymotd",

08 owner => 'root',

09 group => 'root',

10 mode => '0755',

11 require => Package['update-motd']

12 }

Next, I create ./files/misc/10-mymotd containing the following:

#!/bin/bash echo "Welcome to my puppet-managed server!"

In the preceding code, package asks Puppet to install the update-motd package; file asks it to ensure that the file is present and has the permissions as described, but also that this is done after the package update-motd is installed.

The contents of 10-mymotd are placed in a separate file and referenced using Puppet's syntax as:

puppet:///modules/mypuppets/misc/10-mymotd

With only this and a little googling, you should be able to rinse through dozens of services, packages, and configuration files, simply copying from your best configuration into Puppet.

MySQL is just a matter of the mysql package plus your my.cnf file. Setting up /etc/logrotate.d/our-logs with Puppet means you don't have to remember it.

Creating /etc/profile.d/binpath.sh will mean that a customization no one can quite remember (adding s3cmd to the PATH) doesn't have to be remembered. Most stuff on servers is just files, which is what makes Puppet so useful.

The line

require => Package['update-motd']

means that the corresponding file declaration won't be run until the package update-motd is installed.

Puppet doesn't run top-to-bottom but instead compiles a list of dependencies and runs the setup in dependency order.

This approach lets you chain together dependencies and make sure things are installed in the right order. It also means that running puppet apply twice is not the same as running puppet apply on a vanilla system twice, which can be painful for debugging.

I don't have room for the long explanation of this here, but the short answer is: You should use a virtualization tool such as EC2, Vagrant, or VMware to test your Puppet configuration on vanilla systems before you trust them.

Install and Configure Something Useful

So far, I've created a useless file and then created a mostly harmless file and installed a package. Now that I have a small Puppet project, I can install something useful by starting a new project with the following init.pp file (Listing 2).

Listing 2: init.pp

01 package { "apache":

02 ensure => present,

03 name => $apache,

04 require => Exec['apt-get update']

05 }

06 exec { 'apt-get update':

07 }

08

09 file { '/etc/apache2/sites-enabled/000-default':

10 ensure => present,

11 source => 'puppet:///modules/myproject/apache/000-default',

12 owner => 'root',

13 group => 'root',

14 mode => '0664',

15 require => Package['apache'],

16 notify => Service['apache']

17 }

18

19 file { '/var/www/index.html':

20 ensure => present,

21 source => 'puppet:///modules/myproject/web/index.html',

22 owner => 'root',

23 group => 'root',

24 mode => '0664',

25 require => Package['apache'],

26 notify => Service['apache']

27 }

Line 9 changes the default configuration of Apache and creates the 000-default file, which contains:

# Nothing here anymore. # Ubuntu normally has a default on /var/www but we don't want it.

Line 19 creates a document root and puts an HTML page in it. This could be your app or just a holding page, but it gives you a starting point. You need to populate web/index.html with a little HTML – anything you like – then populate the file /etc/apache2/sites-enabled/mysite with:

<VirtualHost *:80> ServerName exampledomain.localhost DocumentRoot /var/www/vhosts/ </VirtualHost>

Now you have a web server config in your Puppet project, and running

puppet apply manifests/init.pp

lets Puppet do the hard work.

What Just Happened?

Once you get into the cycle of writing Puppet code, applying it, and testing it, you'll be more comfortable working with the Puppet system.

A Puppet module, like the one in Listing 2, describes resources: users, files, packages, and services. You go from a vanilla installation to a full configuration by layering resources on top of resources, which means they have to be set up in the right order. These are the dependencies, or meta parameters, as Puppet calls them: before, require, subscribe, and notify.

Puppet only makes changes when changes are needed. If the file exists and looks correct, Puppet won't make the change, but if it looks wrong, Puppet will update the file when you run puppet apply. Puppet configurations are distributed through modules. You'll find a heap of modules at Puppet Labs Forge [1]. With the latest versions of Puppet, you can install these modules so that you don't have to code complex implementations of MySQL by hand [2]. For example, Puppet Labs has master/slave configuration setups.

Learning Puppet

Coming from a database/web app world, learning Puppet was fairly annoying because each test cycle required configuring a machine, so it is important to set up a good test environment. Personally, I like using Vagrant because I can launch a VM and test the Puppet module by passing it to the machine.

If you don't want to or can't test locally, you can use any cloud hosting provider to which you're able to pass boot-up-time commands, such as the user data on EC2. After a couple of hours getting your scripts together, you can bootstrap instances with a single script,

apt-get install -y puppet wget http://<your-domain-with-your-stuff>.com/<your-puppet-module> puppet apply path/to/your/init.pp

which is much nicer than being careful on servers.