The pros and cons of a virtual desktop infrastructure

Desktops off the Rack

At first glance, the benefits of a virtual desktop infrastructure (VDI) seem clear. If you provide virtual desktops, you can centralize almost all of your management tasks on the virtualization server in the data center. That alone offers many advantages. For example, updates lose their terror; after all, you only need to update a few images instead of hundreds of clients.

Conventional software distribution and remote desktop administration are no longer issues. Version incompatibilities and conflicts can be solved at a single point of administration. The processes for providing desktops can be automated to a much greater extent, and backing up user data is much easier because data is stored centrally from the outset.

Virtualization also offers security advantages because you can avoid a dangerous jungle of individually misconfigured operating systems or applications. Hardly anything is stored locally, and the risk of infection is thus zero. Virus scanners or firewalls are not needed on the clients.

You can also dispense with expensive, fully equipped PCs and use inexpensive thin clients that mainly rely on server resources, which in turn achieves more effective utilization. Thin clients also decouple the hardware and software life cycles; never again will new applications force you to buy new desktop computers because the performance of the older generation is no longer sufficient. The thin client, which focuses on input and rendering, is freed from computational tasks and can keep pace over time.

Additionally, thin clients remove some of the administrative load: After a hardware failure, the user simply takes the reserve unit out of the cabinet, plugs it in, and carries on – the admin does not need to be there looking for mistakes and does not need to unscrew the case, restore data from a backup, or reinstall locally. Also, the mean time between failure (MTBF) of a thin client is higher than that of a PC, not least because it has no failure-prone mechanical parts, such as hard drives or fans, which effectively increases availability.

Thin clients also protect the environment because they consume much less power than PCs. Additionally, they can be manufactured in a way that saves energy and materials, and they are easier to transport. According to a study by the Fraunhofer Institute for Environmental, Safety and Energy Technology (UMSICHT) the CO2 footprint of a thin client is 41 percent smaller than that of a PC [1].

The Vendors

The leader in the VDI sector by far is now VMware View (41 percent). Following on its heels is Citrix XenDesktop (26 percent), which is technically on par. However, XenDesktop has the advantage of being able to work with different hypervisors, whereas VMware View is bound to the in-house ESXi server. Microsoft takes a smaller piece of the pie (15 percent [2]) with its Microsoft VDI suite. A remote desktop code-named Mohoro is rumored to being added to the Windows Azure cloud solution no sooner than 2014. A number of small suppliers also take marginal market shares, including vWorkspace [3] and Pano Logic [4].

What VDI Means

When you consider all the benefits, you might expect virtual desktops to be used in environments at least a few dozen clients. The reality is rather different. The thin client breakthrough has been announced several times under different headings and has never really happened. A survey by DataCore of nearly 500 IT professionals around the world showed that more than half do not virtualize any desktops and only 10 percent run more than a quarter of desktops as virtual machines.

This is true for several reasons. For example, virtual desktops have non-negligible drawbacks, and other alternatives can provide almost the same benefits. When discussing the pros and cons, the terminology can get a little confusing; thus, it's worthwhile to distinguish carefully what is at stake. As the name suggests, desktop virtualization virtualizes something, and that always means that resources are not accessed directly (dedicated) but through an abstraction layer. What lies beneath this abstraction layer – the physical world – is hidden from the virtualization user.

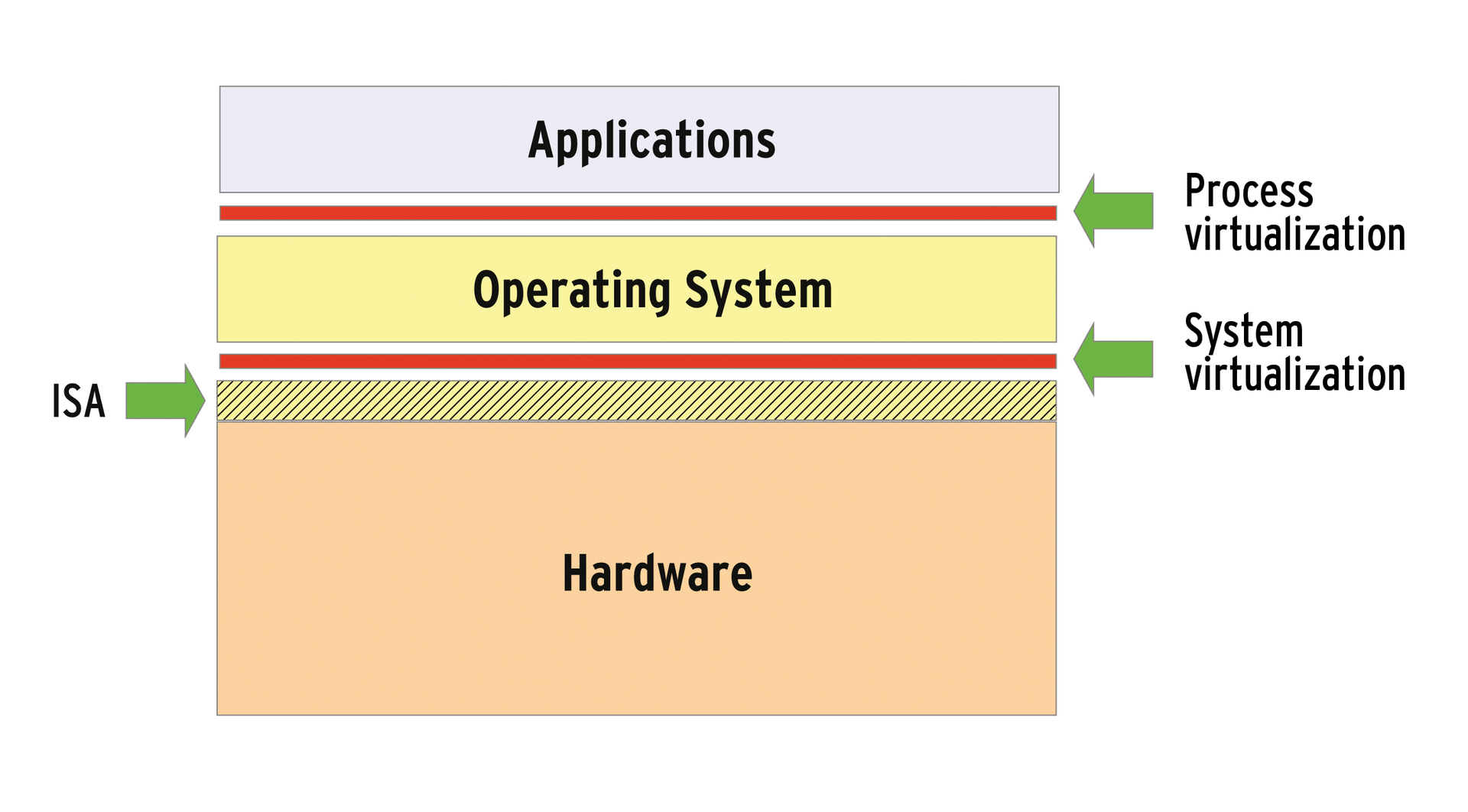

If you consider the classic setup of a computer with the three major components (i.e., hardware, operating system, and applications), then the abstraction layer can reside in one of two places (Figure 1). On one hand, it can sit above the operating system, which is what a terminal server, a VDI alternative, does. Here, all users share the services of a server operating system and its applications. On the other hand, the layer can be implemented on top of the Instruction Set Architecture (ISA), that is, the interface that describes the hardware properties to the programmer (CPU instruction set, registers, etc.). In this case, the operating system runs in a virtual machine for each user. This method is used in desktop virtualization, which is significantly different economically from the terminal server. In this case, each virtual machine generally requires a license for each application.

Virtual machines exist in server virtualization or as virtualization solutions for the desktop, such as VirtualBox. What is special about desktop virtualization? A connection broker is typically installed downstream of the virtual machine to handle authentication, rights management, and load balancing and to provide the connection between the (thin) client and virtualization host. This broker provides the virtual machine to the user.

VMware calls this component the Connection Server; the corresponding component in Citrix is the Desktop Delivery Controller. The desktops can be either individually unique or based on a number of templates. Another difference is the extent to which the user is allowed to customize the desktop. Giving each user their own virtual machine potentially permits a higher degree of customization and, at the same time, also provides better encapsulation over virtual neighbors than a terminal session.

Other components are typically needed. In the case of VMware View, for example, the client must provide the connection protocol between the client and the server; a VMware View Agent running on the guest operating system (Windows) handles this. Here, as with Citrix, user management relies on Active Directory being in place. Finally, a database is used in both cases.

Alternatives

Numerous alternatives to desktop virtualization are available, and the boundaries are pretty much seamless. For example, instead of virtualizing desktops on an entire virtual machine, you can virtualize applications, as the classical terminal server does. The application then runs on the server, and the desktop client handles the presentation.

You can also stream the entire desktop or individual applications to the client and execute them there. Such solutions sometimes use mechanisms that cache the stream locally so that, for example, you can continue working in mobile applications without a server connection. Changes made in the connectionless period are then synchronized back to the server later.

At the end of the day, nothing actually needs to be virtualized; instead, you can run the desktop on centralized physical hardware (e.g., a blade server). Again, a thin client is fine as a workplace. Finally, the simplest alternative comprises managed PCs that are provisioned with an operating system and applications by a software distribution tool. Both run locally on the client.

All of these alternatives benefit from centralization, as already described, and some can also exploit the advantages of thin clients (see the box "Central Administration Is the Greatest Advantage"). However, some of these alternatives share the same drawbacks as desktop virtualization.

Disadvantages

VDI, which appears to be unbeatably attractive at first glance, has one or two drawbacks upon closer inspection. These disadvantages include:

- Costs: Reduced administration overhead saves money, and a thin client is significantly cheaper than a PC. However, you still need to do your sums, because new costs arise elsewhere. For example, additional costs for the VDI software with all the components for the required server hardware, plus storage and network costs, new devices, and the right application and operating system licenses (see the box "We Have Learned Much About Complexity") can easily eat up the savings.

- Server dependence: The direct downside of centralization is server dependence. If the virtualization host fails, nothing works. Thus, you are forced not only to provide a powerful server but to make it highly available. The same applies to storage and the network – they not only create costs, they add complexity.

- Local hardware: If applications require locally available hardware, such as a USB document scanner or an external optical drive on the thin client, you need to research carefully whether you can loop this through the server, because it's not always possible.

- Graphics and multimedia: Graphics-intensive applications, video, and audio are possible with thin clients, but you might need a special client that is more expensive, and you will certainly need much more network bandwidth. Additionally, state-of-the-art transmission protocols such as PCoIP (VMware) or HDX (Citrix), that handle such content more efficiently than the old ICAN (Citrix) and RDP (Microsoft) are the order of the day.

- Morale: Many users feel downgraded if their fully equipped PC is replaced with a thin client that they cannot and are not allowed to manage. Psychological barriers should not be underestimated because, at worst, they lead to inner resignation and staff working to order.

A change from the traditional PC to the virtual PC must be planned carefully by the IT department because it has many consequences.

Side Effects

All resources previously distributed across the users' desks must be available centrally at the data center. This requirement does not simply mean a virtualization server with sufficient processing power – as a rule of thumb, you can expect a maximum of a dozen VMs per core if the workload is not very demanding. It applies in particular to storage for all the virtual disks in your virtual PCs.

Even if each virtual instance only uses 30 or 40GB, this setup quickly adds up to dozens of terabytes, and if you want to back up snapshots of the virtual instances, you need extra space. A SAN is useful, but not cheap. According to an analyst from Gartner, storage accounts for up to 60 percent of the VDI budget [5] – it's not only the capacity but also the performance that influences user acceptance.

The network should not use legacy 10Mb technology, which is often encountered in the form of small switches that are still running, even if everything else has been modernized. Each hardware bottleneck leads to poor performance and thus undermines the acceptance of the solution. Entirely new problems can arise if the desktops need to be delivered via WAN.

All components must also offer reserves and be scalable so that they can be adapted to meet future requirements, and 24/7 availability is a must-have. This requirement also applies to the network infrastructure, which must be redundant and carefully planned so that the failure of a single switch does not take down the whole environment. In some cases, you will even have to think about a geographically separate backup data center, or at least have a backup in another fire zone. At the end of the day, very high availability requirements are the price you pay for centralization.

Desktop virtualization does remove the need for the infamous admin sneakers. In this respect, however, work processes in IT also change. For administrators at the data center, demand increases as the IT environment becomes more complex. The cost of necessary skills training also counts toward the bottom line. In turn, you can possibly save money if you procure the work environment in the cloud as a desktop-as-a-service (DaaS).

Conclusions

Desktop virtualization unquestionably has the potential to contribute to a more efficient, more flexible, and greener IT (see the box "Biggest Advantage – Flexibility"). If the resources are correctly dimensioned, users also experience benefits at the workplace in terms of using a smaller, quieter, safer, less sensitive, and easily swappable device. To what extent all of these considerations make business sense is a completely different question. Whatever the answer, this brave new world does not come free of charge. Thus, you not only need to consider servers, storage, and networks, but also the increasing complexity and demands on the data center administration. Despite all your efforts, the equation might not balance out and return financial benefits. It is most likely to succeed in environments with highly standardized jobs and a manageable number of applications without extensive multimedia or graphics use. The expectation that VDI will blast all physical PCs into a black hole is deceptive.