Cloud Orchestration with Cloudify

Music Maestro

A new generation of orchestration tools is rising to the challenge of configuring VMs in complex, real-world scenarios. Cloudify [1] is an orchestration solution that promises customers an easy and uncomplicated approach to leveraging the benefits of services in the cloud.

With other tools, such as Chef or Puppet, admins can build a cloud environment from scratch with just a few mouse clicks. The cloud platform takes care of the details, leaving the users to just start and stop the VMs.

Although starting and stopping VMs might not seem like very much work, it can quickly escalate, especially when customers want to put the features of a cloud to optimal use. For example, assembling an environment for web servers would mean starting the individual VMs from the designated images and spending a full day configuring them. If you turned off this configuration and needed it again a year later, the work would start all over.

Chef and Puppet only work well with more static setups, where it's clear in advance what the configuration should look like at the end. The open source Cloudify truly automates the process of configuring VMs in the cloud, supports various types of public clouds, and is under active development.

Start as PaaS

GigaSpaces, the company behind Cloudify, began developing the tool in 2012. Cloudify was originally designed as a tool for Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) applications (although the boundaries to SaaS are fluid). The basic idea was to give users a quick and easy way to start specific programs or services within a cloud computing environment.

Currently, Cloudify targets customers who launch prebuilt appliances in cloud environments and want to operate their own services quickly without dealing with the technical underpinnings. The vendor offers prebuilt templates and images that you can enable in Cloudify to run the commands stored on them in a cloud.

Under the Hood

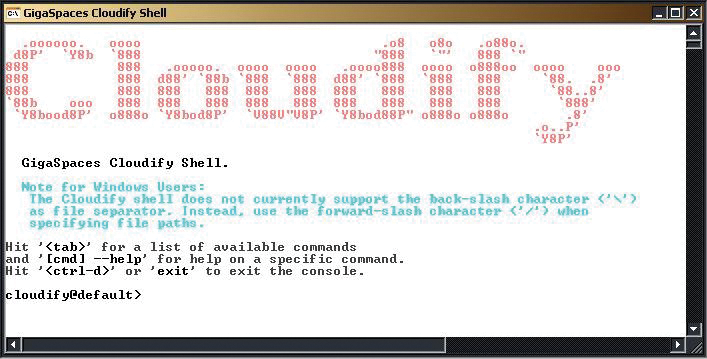

You can experience Cloudify for yourself relatively easily if you run Windows or Linux on your system. The Cloudify website offers you the option of downloading Cloudify to a local hard disk and running it as a local cloud (Figure 1).

For a better understanding, it is important to know that Cloudify itself is always present as a separate instance within a cloud. No matter how you design your configuration, Cloudify needs to operate through a master VM. In the case of a local cloud, the master VM runs on the local machine. Cloudify handles the complete bootstrapping of its own local cloud, which does not require access to a public cloud provider and thus imposes very few requirements.

The Cloudify tarball is a heavyweight at 160MB, but the user initially only has to interact with precisely one component: the Cloudify shell, which gives admin the ability to send specific commands to Cloudify. The Cloudify shell is important because Cloudify itself receives its commands from a RESTful API. The shell sort of translates commands from users to JSON format, thus enabling the effective use of Cloudify. Incidentally, the rest of Cloudify is in Java and thus requires a current JDK (Java Runtime Environment is not sufficient, as the Cloudify developers explain in the documentation).

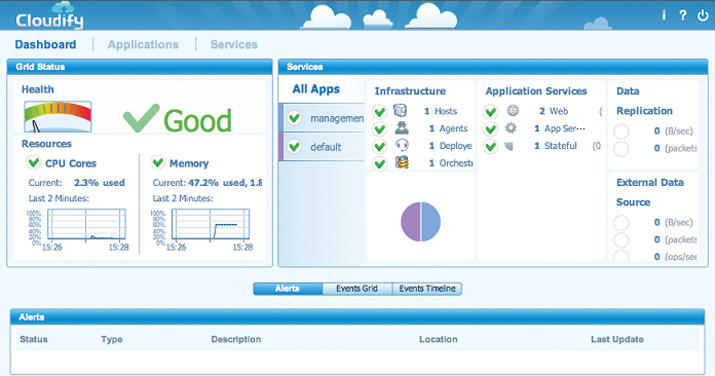

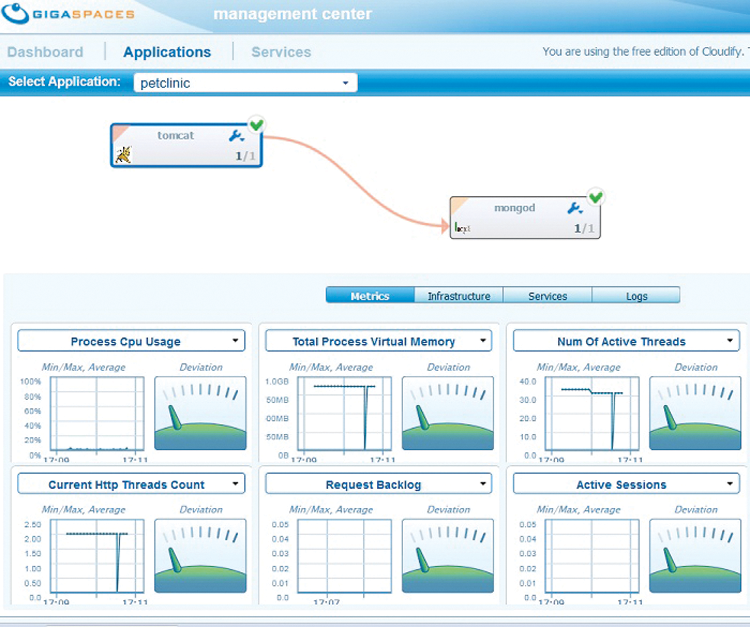

If bootstrapping of the initial cloud works, whether as a test installation on a local system or a genuine deployment in a public cloud, the Cloudify web front end is then available (Figure 2). The front end has the ability to start PaaS deployments; you can also discover the performance values of the current deployment and extract monitoring information. The web interface always runs on the management VM, which admins will most likely prefer to the Cloudify shell because it works in any web browser.

Modular Structure

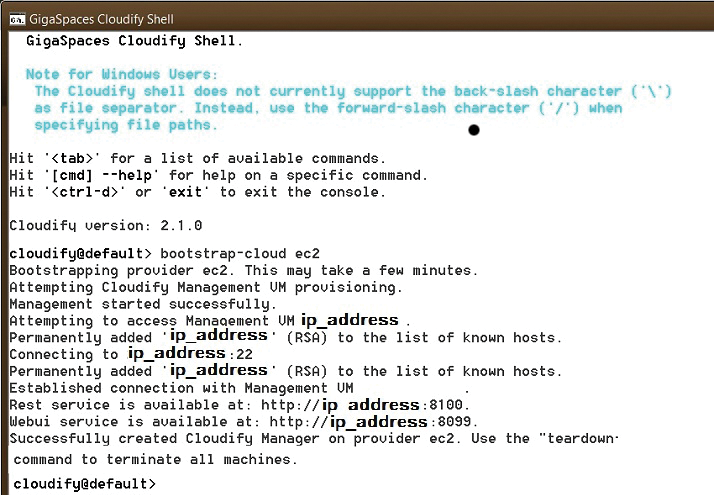

Cloudify consists of many parts, and the modularity of the solution continues down through the individual components, which in turn consist of several subcomponents. The main engine handles communication with a specific public cloud through its own "cloud drivers" (Figure 3).

This design helps users who want to use Cloudify to handle the orchestration of VMs in public clouds – which is probably the vast majority of Cloudify users. The list of supported clouds includes all the key players: Amazon, Rackspace, Microsoft Azure, and everything that is compatible with OpenStack. With the same instance of Cloudify, it is possible to manage multiple public cloud access points at the same time. Even multitier clouds that span multiple cloud environments are possible.

Cloudify includes some features that make using the tool a very pleasant experience. Among other things, you can define load limits for individual PaaS applications. During operation, the Cloudify master instance uses its own logic to discover the load generated by the PaaS application on the VMs. If the current load exceeds the limits set by the admin, Cloudify automatically makes sure that more instances of the application are started. This feature keeps the load time for users of the app at a tolerable level; however, the system is automated, thus requiring no intervention on the part of the administrator.

Recipes

Cloudify organizes configuration templates into recipes. On one hand, you have the application recipes – in Cloudify, an application is a generic term for all the services necessary for operating the application. For example, if you wanted to run a web platform that included phpBB, the recipe might go by the name of phpBB.

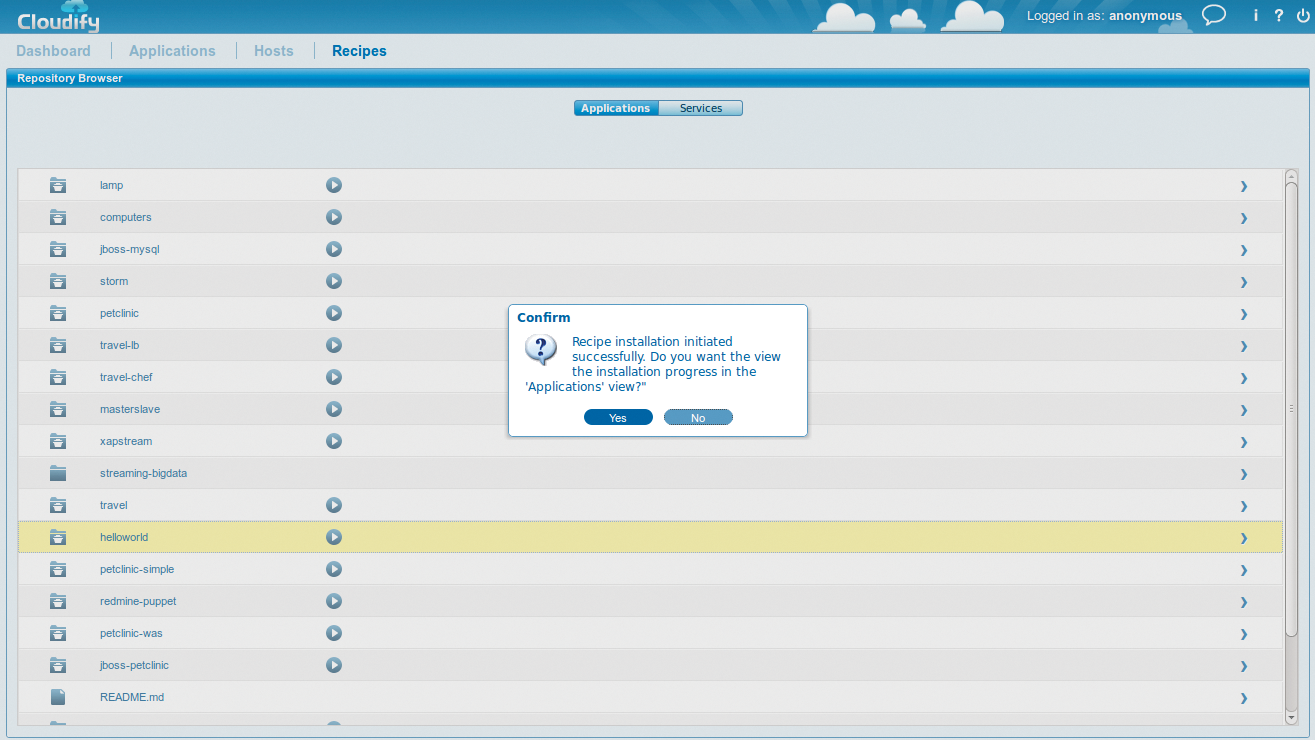

An application recipe consists of the definitions of several services that are necessary to achieve a specific purpose. For example, a phpBB service might require additional services such as MySQL. For a service to be manageable in Cloudify in the scope of PaaS, you thus need an appropriate service recipe; a cornucopia of recipes for most popular applications is available online [2] (Figure 4).

If you want to offer your customers the opportunity to run a web server, say, for their own blog, you will probably be happy with these prebuilt recipes. However, if you want to automate the process of deploying specific services in the cloud, you have reached the point where you will need to develop your own service recipe.

Service recipes have a relatively complex anatomy; for example, they support lifecycle events that are more important than they might seem at first sight. Ultimately, lifecycle events do whatever is essential for the deployment of a PaaS application: They ensure that service recipes follow the appropriate commands – triggered by specific events, such as starting and stopping an application. In other words, a recipe for the Start lifecycle event would need to ensure that the program is installed and started.

Terminology is important. The Cloudify developers distinguish between services and service instances in the application context. A service instance is a concrete incarnation of a service, whereas the term service refers to the instances of the same service available throughout the cluster. "MySQL" as a service thus refers to all instances of MySQL that belong to a Cloudify application; a service instance, however, would refer to a specific instance of the service that is uniquely identifiable.

All told, the concept of recipes in Cloudify is comprehensive and, in the beginning, undoubtedly complex. If you need a helping hand, check out the Cloudify documentation [3], which also contains case studies for the most important topics in addition to detailed explanations. For example, GigaSpaces describes in detail how you can use recipes to set up a Tomcat or a MongoDB system as a PaaS.

Integration with External Tools

Although Chef takes care of hosts rather than specific applications, the Cloudify developers leverage the power of Chef as a central management tool. Since Cloudify 2.2, it has been possible to use Chef to deploy applications on virtual machines. In fact, most of what you will find in Cloudify recipes can be achieved by integrating Chef Cookbooks.

Looking Forward: Cloudify 3.0

The current Cloudify version 2.6 has already been around for some time. GigaSpaces is working hard on a new version 3.0. Cloudify 3.0 will be a major upgrade, largely written from scratch. One reason for the major change is a strategic realignment directly related to the OpenStack project.

OpenStack support in Cloudify has plenty of room for improvement; this was to a large extent because OpenStack failed to issue clear guidelines for orchestration.

OpenStack Havana, however, has introduced a component called Heat that supports orchestration based on several different formats. Heat is basically a template-processing engine that reads environment descriptions on one side and then implements them on the cloud side. What does this mean for Cloudify? After all, the Heat component basically does exactly what Cloudify previously did, and in a very similar manner. Is it still worth putting time and effort into adapting Cloudify for OpenStack?

The developers believe it to be so: Cloudify 3.0 is drifting very clearly in the direction of OpenStack, according to information provided by GigaSpaces. Of course, Cloudify 3.0 will continue to support other cloud systems; the solution will therefore not become a piece of "OpenStack-only" software. Yet, Cloudify 3.0 will be closely meshed with OpenStack – and this includes support for all APIs in OpenStack. Additionally, Cloudify 3.0 will not duplicate the functions that already exist in Heat; in fact, Cloudify will simply pass on the required steps to Heat, which will provide seamless integration of the two tools.

Also, the GigaSpaces developers are expanding the Cloudify policy engine. In Cloudify 2, the policy engine is responsible for ensuring horizontal scalability. The basic idea is to create definable workflows that carry out certain actions, triggered by specific events

Another major step in Cloudify 3.0 is a change in programming language: The tool has undergone a rewrite in Python, which is also probably attributable to the desired closer ties with OpenStack.

Conclusions

Cloudify 2 is a very useful tool for effective orchestration across the borders of different clouds. The possibility of creating multitier clouds in particular makes administrators happy, because it allows them to manage VMs across the boundaries of individual cloud providers without troubles. Options such as automatic horizontal scaling are useful for applications in the cloud and even ensure that applications remain online when exposed to heavy load (Figure 5).

The solution benefits because Cloudify really does remain faithful to the PaaS motto: Everything that happens in Cloudify happens on the basis of specific apps and not on the basis of the VMs on which the apps run.

That said, some design concepts implemented in Cloudify 2 do not exactly provoke an enthusiastic response. The fact that the service is based entirely on Java will not go down well with many admins. Additionally, it will probably take a while for admins to be happy with the system of recipes in Cloudify. The fact that you can use Chef as an alternative is a good thing.

Cloudify 3.0 holds a great deal of promise, even if only a small demo of the tool was publicly available when this issue went to press. Cloudify 3 has the potential to be an important component, especially for OpenStack setups.

GigaSpaces apparently sees the future of Cloudify to be tied to the OpenStack context, but the company promises to keep the features for other clouds and continue to support them. One thing is for sure: Anyone looking for a useful tool to maintain PaaS components as part of a public cloud should definitely take a look at Cloudify.