History and use of the mail utility

Magical Mail

A good pedigree is an important aspect of a software package for several reasons – especially if the software is installed on a valuable server. Often, it will help ensure that operational facets of the package have been carefully considered, such as its integrity, reliability, compatibility, and security.

I mention a package's pedigree because I recently stumbled across a tiny piece of software that I used extensively some years ago, and it reminded me how steeped in history that package was. Despite its diminutive size and unquestionable sophistication, it is shrouded with confusion harking back to its provenance.

Along with other key services associated with the Internet of the past, historians looking back will always include email as a cornerstone. Without email, the Internet might not have gained as much traction and might have failed to conjure the staggering uptake it has achieved.

With that in mind, you might consider the inbound and outbound aspects of email at a more technical level, and how the Post Office Protocol (POP) in its various versions and incarnations was all pervasive until a few more features were required, such as encrypted login details. This was just one of a variety of reasons that the Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP) gained popularity. Also, I would be remiss not to include the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP), which surfaced as far back as 1982 and still remains the champion for outbound email on today's very different Internet.

As a sys admin, providing services so that end users might enjoy picking up and sending email messages is a relatively well-documented procedure. Popular mail servers and mail clients slot together nicely, and the docs read clearly and concisely.

Consider, however, when you need do something slightly off-piste and a mail client won't just plug straight into an out-of-the-box mail server's services to solve your problem. Sys admins since time immemorial have hand-crafted scripted solutions for abstract issues and then emailed the results to a number of people. On Unix-like systems, the magical utility that does one thing and does it well (with a doff of the cap to the Unix philosophy), in terms of communicating efficiently with a preconfigured SMTP server, is the mail utility.

It's important to note that throughout the history of the mail utility confusion has reigned. That's the understatement of the day. Thus, when I reference the "mail utility," I am more than likely referring to the modern mailx or similar utilities, because few systems use the older, deprecated versions.

In this article, I'll look at how the magical mail utility has evolved, somewhat dramatically, over the years and explore some ways in which you can integrate it with simple, day-to-day, sys admin command-line tasks along with adding it to your scripts.

Enough with the Scenarios Already

I'll begin with some simple examples and scenarios. Imagine you have just spent a morning working with screeds of headache-inducing, fiddly text files containing comma-separated this and tab-delimited that. Finally, you've reached a point where you think your boss will be suitably happy with the result, and you breath a sigh of relief. Then, it occurs to you that you've been working on a remote server and the resulting text file is about 8,000 lines long, several columns wide, and you don't have an easy way to retrieve it from the remote server. Copying and pasting just won't cut it.

The epiphany dawns when you realize that you can email the file to yourself directly from the server. Step forward the mail utility.

In its simplest form, the mail utility lives in /usr/bin/mail, and if you want to send an empty email with just a subject line, you could populate the body of the email with a reference to /dev/null. The -s switch allows a subject line to be specified (although even such a simple feature isn't available on the oldest versions).

# mail -s "Subject Matter" chris@binnie.tld < /dev/null

The outcome of this command is an email with an empty body, but otherwise a perfectly formed email is sent (as long as you've configured an SMTP mail host to point your server at, which I will assume is done for now and explore further a little later).

As much as I enjoy sending myself and others brief email messages with short subject lines and empty bodies, at some point, I'll want to add some text to the email body, so first I'll look at how to enter text into the body field by omitting the /dev/null reference.

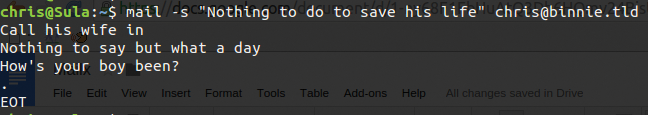

You can enter text arbitrarily (even by copying and pasting) and then tell the mail utility that you've finished the body of the email by entering a dot on a new line, which is translated as EOT, meaning "end of transmission" or "end of text." This triggers the sending, which means the mail is shipped off right away. You can see in Figure 1 how this might look on a command line.

More pragmatic readers might be thinking about how to send a file that is not typed into the email directly. You would be forgiven for desiring such functionality. For simple text files, you would "insert" text (note that it's not an "attachment") from a previously created file into the body of your email:

# mail -s "The one and only Billy Shears" chris@binnie.tld \ < file_full_of_lyrics

Another simple option for a super-short message might be achieved with this method, too:

# echo "The act you've known for all these years" | mail -s "Cellophane \ flowers of yellow and green" chris@binnie.tld

Now, back to the frustrating scenario that is threatening your employment status. The problem often encountered with the less modern mail utility is that of "attaching" files to an email and not just "inserting" them (although the methodology I demonstrate is not really an "attachment" as it is perceived today). Thankfully, there's a simple solution that I will come to in a moment.

For now, please take it on faith that to use the mail utility in any sensible way you are probably going to need to install its feature-filled successor heirloom mailx or at least mailx. The former is a fully featured MIME-enabled mail client (MIME stands for Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions). Simply put, heirloom mailx will happily attach files for you without any rigmarole.

If you're curious, the package actually used to be called nail, but I'll explore its history later. Assuming you're looking at a modern Linux operating system, the complexities of which command to use and which features are available to you (depending on which package is installed: mail, mailx, nail, or heirloom mailx) can be put to one side.

Debian/Ubuntu users can install it as follows:

# apt-get install heirloom-mailx

The package description aptly describes the package as "feature-rich BSD mail" – which sums up its raison d'être nicely. Far from just being able to send email from the command line, heirloom mailx can spin plates and dance a jig, too. Next, I'll peer into its provenance in more detail.

Wake Up, You at the Back

All the way back to well before Sinclair C5s were the rage – 1971 or so – an early edition of Unix incorporated a command called mail. So nascent was this embryonic operating system that it couldn't speak to other machines; thus, mail was more like the write or talk commands in the sense that you could send lines of text to other users on the system that you were logged in to.

The talk command (for those unfamiliar it) could be used to speak to users on your machine or remotely on other machines. I certainly don't want to get into the intricacies of a chicken-and-egg debate, but I think it's of interest to show how similar the two commands are for comparison.

For example, to speak to someone on the same machine, you could use:

# talk pepper

If networking of some sort were present, you could use this command:

# talk rita@some_other_machine

Rather than examining the mail utility's rich history in detail, I will skip rapidly onward. In brief, the mail utility grew a number of arms and legs and eventually included an interactive shell of sorts that could speak to local mailboxes. During this evolution, the mail utility also learned to speak to varying SMTP servers, such as the most popular, and undoubtedly archetypal, Sendmail.

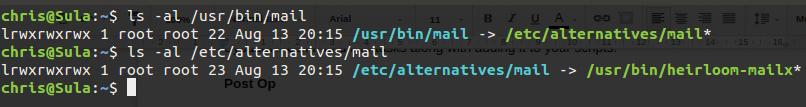

Having mercilessly skipped the tool's rich tapestry, I feel somewhat vindicated by the example below. As mentioned, it's an understatement to say that the mail utility's background is an age-old, bubbling cauldron of confusion. Here's that example, shown in Figure 2.

heirloom-mailx command.Anyone, Anyone

Now, I'll return to that scenario in which you need to attach some relatively large files to an email directly from your server, and, for whatever reason, a modern version of the mail utility is not readily available.

Can you guess what obstacles might need to be surmounted before you can attach certain files properly? The example scenario involved manipulating large amounts of text, but what about attaching an image file like a JPG or a smallish binary, such as the /usr/bin/mail command, which is about 350KB in size?

Before mail clients had all the requisite capabilities necessary to send files across the Internet, the files had to be encoded (wrapped or encapsulated) in a way that could then be easily unwrapped at the other end. In its simplest form, the excellent uuencode command can do exactly that. So that you can see it in action, I will show you a tiny script in a second.

First, here's a reminder how you would send plain text in the body of an email:

# mail -s "Filling in a ticket in her little white book" chris@binnie.tld \ < text_in_the_body

If you did that with an image file, you would effectively insert it into the body making extra copying and pasting work for the recipient. The email would just appear nonsensical to a mail client upon receipt if it was sent like this:

# mail -s "Sitting on the sofa with a sister or two" chris@binnie.tld \ < bad_idea.jpg

Incidentally, you might need to install uuencode (around 142KB) as follows with the sharutils package:

# apt-get install sharutils

To use uuencode alongside the outbound email functionality, you can use the mail utility like this:

(cat EdgarAllenPoe.txt; uuencode ringo.jpg first.jpg; uuencode \ george.jpg second.jpg) | mail-s "Expert textpert choking smokers" \ chris@binnie.tld

Take a look at this command more closely. Before the pipe, I've enclosed the commands in brackets to be fastidiously neat (and they're needed, actually). You're likely familiar with the layout of the commands after the pipe, so take a look inside the brackets. The text file is first presented to the mail utility. That cleverly gets picked up as the body of the email.

The uuencode options appear to be written incorrectly at first glance, which is why I'm drawing your attention to them. The ringo.jpg entry is the local file name of the attachment that you're picking up, and the first.jpg entry is the file name that will be presented to the email recipient. This action is rinsed and repeated for george.jpg and second.jpg and then piped into the mail command with a -s for the subject, followed by a recipient's email address.

A few CPU cycles later, you should see the results either in your logfile /var/log/mail.log or your inbox – if you've emailed yourself for the test. If all went well, included are the binary attachments with the correct file names and a well-formed email body.

I promised to show you a very simple script to bundle up lots of attachments for inclusion with an email – a reminder that email was never designed to be used for large attachments, which is a perennial discussion I seem to have with end users. As a guide, one well-known and widely adopted webmail provider currently limits 20MB as the outgoing file size for its SMTP, per email. I tend to be stricter and limit the size to 10MB on a smaller infrastructure.

If you want to test this method, you can run the touch command to create a few empty JPG files, as I have here (you should test with a real JPG image later to confirm it's working):

# touch {1..5}.jpg

I have filled up a text file called file_list with a list of JPGs in my directory as follows:

# ls *.jpg > file_list

I also created a file called bodytxt, which contains the text content of my email, as you might have guessed. Make the script shown in Listing 1 executable with

Listing 1: Bundling Attachments

#!/bin/bash

files="file_list"

( while read uniq; do

( uuencode $uniq new.$uniq )

done < $files; cat bodytxt) | mailx -s "Go to a show, you hope she goes" chris@binnie.tld

exit

chmod +x scriptname

and try it yourself with ./scriptname. The new file names arrive as attachments named new.1.jpg, new.2.jpg, and so on.

You could potentially attach a hundred, tiny, uuencoded image files to an email very swiftly with a method like this. As ever with shell scripts, your mileage might vary, but you can easily adjust this method to send an email for each attachment, too.

There Must Be an Easier Way

Now for a deep breath. The modern heirloom mailx (and other mail clients for that matter) lets you skip that painful process with an unfathomably easy -a attachment parameter, as follows:

# mail -x "Not just anybody" -a 1.jpg chris@binnie.tld

It really is that simple. With what you've learned, however, if you're ever caught out by MIME types or base64 encoding headaches on older operating systems, then you'll be suitably armed to circumvent the issues in the future.

How does the modern mailx manage this? It automatically alters its content type by looking into the file for MIME types or by file name extension (e.g., .jpg). You might expect a JPG image to have a MIME, such as jpeg image/jpeg or similar. If the mail utility can't fathom what type of file the content belongs to, then it will use text/plain or application/octet-stream as a fallback.

Tangential Tinkering

Before getting distracted with another facet, I might mention some of the other basics for sending email from the command line using the (modern) mail utility. You'll be glad to know that they're very simple to enable.

Formatted as comma-separated lists, you can use the -b parameter for blind carbon copying (BCCing) and -c for carbon copying (CCing). You can throw in -d for debugging, which conveniently doesn't send the email message but steps through all the motions as if it were going to. With debugging enabled (having pressed the "dot" key and Enter to trigger EOT), I see this:

user = chrisbinnie, homedir = /home/chrisbinnie . Sendmail arguments: "send-mail" "-i" "chris@binnie.tld" "chris@linux.tld"

The linux.tld address is my CC address, and the primary To: address is the binnie.tld address.

According to the man pages, the debugging option "is intended for mailx development only." Fear not, however; Listing 2 shows how powerful the verbose or -v option is. I think it's absolutely fantastic.

Listing 2: Verbose Mode

[<-] 220 mx.google.com ESMTP t2fjm4427fd213ply.2523 - gsmtp

[->] EHLO smtp.box.tld

[<-] 250 SMTPUTF8

[->] STARTTLS

[<-] 220 2.0.0 Ready to start TLS

[->] EHLO smtp.box.tld

[<-] 250 SMTPUTF8

[->] AUTH LOGIN

[<-] 334 VXNlcm5hbWU6

[->] Y2hyaXNiaW5uaWUzQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

[<-] 334 UGFzc3dvcmQ6

[<-] 235 2.7.0 Accepted

[->] MAIL FROM:<chris@binnie.tld>

[<-] 250 2.1.0 OK t2fjm4427fd213ply.2523 - gsmtp

[->] RCPT TO:<chris@binnie.tld>

[<-] 250 2.1.5 OK t2fjm4427fd213ply.2523 - gsmtp

[->] RCPT TO:<chris@linux.tld>

[<-] 250 2.1.5 OK t2fjm4427fd213ply.2523 - gsmtp

[->] DATA

[<-] 354 Go ahead t2fjm4427fd213ply.2523 - gsmtp

[->] Received: by smtp.box.tld (sSMTP sendmail emulation); \

Sat, 12 Mar 2018 17:47:29 +0000

[->] From: "Chris Binnie" <chris@binnie.tld>

[->] Date: Sat, 15 Nov 2014 17:47:29 +0000

[->] To: chris@binnie.tld

[->] Cc: chris@linux.tld

[->] Subject: Picture yourself, on a boat, on a river

[->] User-Agent: Heirloom mailx 12.5 6/20/10

[->] MIME-Version: 1.0

[->] Content-Type: multipart/mixed;

boundary="=_546791b1.cwvb6n4KoGN8/hpZ+3JYeQN7+d1wNr6+lHmtxFOfJlKkkY3o"

[snip ...]

As you can see, an entire email transaction is taking place before being released into the wild on the Internet. I have snipped the Content-Type: image/jpeg section with the MIME information and the gobbledygook that is presented in place of the binary JPG file.

The information in Listing 2 allows you to trace each stage through the transaction; note that I'm using authentication to connect to Gmail, which is accepted successfully. I'm also using a Sendmail clone to package up my SMTP requests rather than installing a full-fledged SMTP server. I'm utilizing the services of the super-lightweight and highly versatile sSMTP software to speak to Gmail directly via the mail utility.

Finally, there's an address CC'd, and I'm emailing the same address (displayed as the To: line) that I'm sending the email from. The process tails off with the aforementioned MIME information and shows the mail client version with:

[->] User-Agent: Heirloom mailx 12.5 6/20/10

A handy -E switch, also known as the skipemptybody option, is ideal for scripting. Here, the mail utility will quietly ignore email with empty bodies, as is its prerogative. You might want to use this for one-line entries in the crontab, where you want email with content but also just want to ignore them if there's nothing to read after various system events.

For such a scenario – wherein you use cron to report dutifully to you if there's something to report – you might want certain preconfigured variables set up in advance. You can do this with a config file called /etc/nail.rc.

Dare I repeat the statement about the utter chaos caused by so many hats being thrown into the ring when it came to developing the mail utility? Even the excellent heirloom mailx still uses that file name, referencing nail, for its config. At least the headers of the nail.rc file provide a kindly reminder of which application this config belongs to.

Within that file, you'll find a mixture of interactive shell commands and a sprinkling of options for command-line email. Spend a moment rummaging inside if you want to learn more. Not listed on my Ubuntu version are the following options:

set smtp=smtp.box.tld set from=sysadmin@linux.tld

You might want to add these lines to adjust where the mail comes from and which SMTP relay to use. For integration with Gmail (and be warned that mileage will almost certainly vary because of version subtleties), your config file might look as follows:

set smtp=smtps://smtp.gmail.com:465 set from="Chris Binnie" set smtp-auth-user=chris_binnie_linux set smtp-auth-password=my_password set ssl-verify=ignore

Rather than using the config file, you can also pass these parameters sensibly to the command line, as I've been doing. I've kept it simple and left out a lot of the parameters, but I'm sure you get the idea.

Config files exist for a reason: to avoid having to rewrite the Magna Carta as a massive, single command line:

# mail -s "Made the bus in seconds flat" chris@binnie.tld \ -S ssl-verify=ignore -S smtp-auth-user=chris_binnie_linux < bodytxt

Before modern versions of mail clients existed, consistently porting hand-crafted scripts from the command line between systems (and versions of the mail utility) was problematic. Remember, for example, that the -s for changing the email subject line was not supported universally, and I'm sure that you'll agree that's a relatively fundamental component of sending email. More difficulty resulted from the fact that altering the From: line, or who the email was sent from, wasn't always easily possible.

A scenario might have been, for example, that you had Bash installed on a Solaris box and also on a Linux box and knew your scripts were solid. However, because of the packages bundled with the operating systems, you always had to be mindful of altering your scripts or, more than likely, overwriting versions of the mail utility by compiling them from source to get them to send your system reports reliably.

Another Subtitle

I remember having all sorts of issues with a Qmail MTA (Mail Transfer Agent) trying to get it to accept a change in the From: line. I can do this on my current setup (remember that I'm using sSMTP as a conduit to speak to Gmail's SMTP servers) with the following settings. On the command line, I can use:

# echo "Four thousand holes in Blackburn, Lancashire" | \ mail -r chris@linux.tld -v -s "Dragged a comb across my head" chris@binnie.tld

This replaces the From: line with chris@linux.tld. Be warned however, if you're delivering it to some email providers, they will ignore the From: line and replace the account the email has been relayed through to protect against spam.

If you're interested, you can install sSMTP as follows:

# apt-get install ssmtp

The configuration that is working for me is shown in Listing 3 and lives in the config file /etc/ssmtp/ssmtp.conf. I've abbreviated the less salient entries and other comments for the sake of brevity.

Listing 3: sSMTP Configuration

# The place where the mail goes. The actual machine name is required, no # MX records are consulted. Commonly mailhosts are named mail.domain.com mailhub=smtp.gmail.com:587 # The full hostname hostname=linux.chrisbinnie.tld # Are users allowed to set their own From: address? # YES - Allow the user to specify their own From: address # NO - Use the system generated From: address FromLineOverride=YES AuthUser=chris_binnie_linux@gmail.com AuthPass=my_plaintext_password UseTLS=YES UseSTARTTLS=YES AuthMethod=LOGIN

Author Caveat

Warning: If you use Gmail as I have done, you should note that your password is kept in plain text within the sSMTP config file. To secure it, you should do the following to allow only root access to that file:

# chown root:mail /etc/ssmtp/ssmtp.conf # chmod 640 /etc/ssmtp/ssmtp.conf

Note the file group mail in the example may differ from your installation's group.

You can alter your own user group permissions allowing you access with the following,

# usermod -a -G mail chrisbinnie

where obviously chrisbinne is my username. You then need to log off all of the terminals that you have open to that server. With some trial and error, you can then send a test that works and in that way help protect your plain text password a bit more.

So Many Ss

Although sSMTP is a send-only Sendmail imitator, it has struck a fine balance, again following the Unix philosophy of doing one thing well. That Zen-like balance is one of simplicity and sophistication. It should solve a number of problems in which you cannot or prefer not to install an MTA but still need your outbound mail to behave reliably.

The excellent sSMTP is designed to allow both humans and software to send outbound mail. Besides the ssmtp.conf file, it is also intelligent enough to listen to a revaliases file from the same directory. Reverse Aliases allow a number of users to change their sender email address (their From: line) automatically.

A common headache for sys admins looking after many servers is that lots of system email is triggered by root@hostname.domainname.tld. Depending on how you set up your alerting and mail filters, it's sometimes preferable to have the service name as the sender – something along the lines of www3-failover@domainname.tld or ntp@time.domainname.tld, for example.

The format for such a file is as follows:

root:mail@cluster42.binnie.tld:external-sysadmins.smtp.tld ntp:stratum-1@ntp.binnie.tld:local-sysadmins.smtp.tld:2525 snort:security@binnie.tld:all-sysadmins.smtp.tld

The optional second element that appears after the first colon is the potentially different SMTP server to punt the mail through; it might be only local or on your LAN, for example. As you can see, you can request port TCP 2525 for localized deliveries, too, or any port for that matter.

On startup, you can pass a few config parameters to sSMTP, such as instructions to ignore all IPv6 addresses with the -4 switch or, conversely, -6.

Additionally, you can pass a login and password along with the command line (be wary), among other options. It presents quite an old-fashioned shell of sorts. You can trigger it with something like this:

# ssmtp chris@binnie.tld

You can send email after writing that into the command line and hitting Enter with this input format:

To: chrisbinnie@linux.tld From: chris@binnie.tld Subject: Hello, Hello You say goodbye and I say hello

To finish the email, hold down Ctrl+D.

To add an SMTP authentication username to the command line at the start of this process, you just add

-auchrisbinnie -appassword

replacing chrisbinnie, obviously, with your username and putting -ap in place before your password.

Again, be wary about passing command-line passwords and be sure that you want to expose your credentials in Bash history or other places. Finally, you can adjust -amCRAM-MD5 or LOGIN for the authentication scheme in use.

Just like the marvelous mail utility, you can add a debug parameter with the -d2 option, where the number is the level of debugging detail. Mix up your options with a human sender name, such as -fChrisBinnie. By using the -v verbose mode, you can see that the mail utility sits very comfortably alongside sSMTP.

Clearly, the outbound MTA needs to fulfill its obligations for the mail utility and sSMTP to function correctly; if you don't monitor your outbound mail servers, then you probably should. With monitoring in place, you will be able to tell why system reports or other email doesn't get sent or received successfully.

End of Transmission

I have reached the EOT signal. In this article, I offered a smattering of history along with some insight into the extensive functionality of the mail utility in its modern form.

Outbound mail is used in almost limitless scenarios, whether it's for backing up tiny logfiles, for the safe-keeping of config files remotely, or for reporting system events – let alone for users to communicate. I hope you now feel suitably proficient with the command line's outbound email idiosyncrasies and feel confident enough to tackle any tricky situations that arise on both ancient, arcane operating systems and modern versions.