The Final Technology Frontier: You

I've watched many things drop from sight during my lifetime. Some are simply reminders of days past, such as mailboxes on the street, pay telephones, and vinyl record albums. Some of the innovations that have disappeared, however, have had a more profound effect on me, such as rotary dial phones that gave way to push-button phones, compact discs that gave way to downloadable music, and camera film that gave way to digital blips on a computer screen. The point is that all of the innovations I've seen during the past couple of decades have been made to make my life easier or richer in some obscure way. But the next generation of inventors isn't just thinking about the external environment: They have turned their sights toward you and me – in the years ahead, the consumers won't just use the product, they will become part of the product.

We are the technological final frontier. It begins with small things, like a smart watch or a headset that measures your body temperature and evolves into something that, until a couple of years ago, was the stuff of science fiction. I'm describing the next revolution in human development: implanted technology. We've had pacemakers for years, but I'm telling you that someday in the future people will have nanoscopic computers implanted into their bodies that provide constant feedback on a number of parameters.

I'm OK with body temperature, blood pressure, galvanic skin response, hemoglobin, electrolytes, blood sugar, and the like being measured passively throughout my day. However, I don't really want my exact location to be known always through the magic of technology. I'm not sure why I don't; I just don't. It seems like an invasion of privacy.

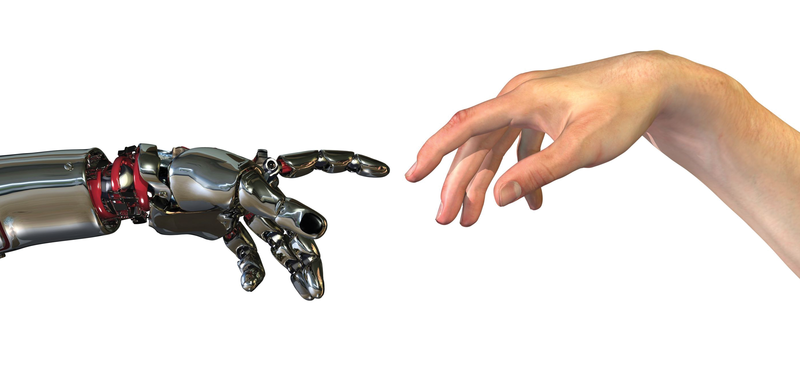

The news isn't all bad, though. Implant technology could allow people to see, hear, run, work, or ride a bicycle without the use of external prosthetics or painful surgeries. Recovery times would be very short or even nonexistent. But where do we draw the line between human and machine? How much of me can be technology before I become an android or a cyberman (thanks Doctor Who). How will I know where I stop and the technology starts?

The answer is that I might never know. And then, there's the question of quality of life. How much of me can be techno-gadgetry before I begin to suffer, not as a human, but as a machine? It seems farfetched now, but in a few years, we will face the question of how much we want to be our technology.

Ken Hess *ADMIN Senior Editor