DIME and Dark Mail seek to change the world of digital mail

Secrets

Ladar Levison may be an unfamiliar figure except to a few people in the community, but many are familiar with his former company: Lavabit, which was in business from 2004 to 2013. Lavabit was a pioneer in the field of secure email; it was founded with the goal of serving as a secure email provider.

Lavabit's Vulnerability: The Customer's Key

Lavabit really did set standards at the time: Asynchronous encryption was part of the standard – with a quality that even secret services had trouble breaking. The solution had one vulnerability, though: The key that Lavabit used for the crypto part of the installation was stored by Lavabit itself, on its own servers. Lavabit's customers needed to trust the company because Lavabit could always read the content of the email that a customer sent via its service. This functional approach did more than just scare off people with a certain affinity for encryption – it proved to be an existential problem for Lavabit.

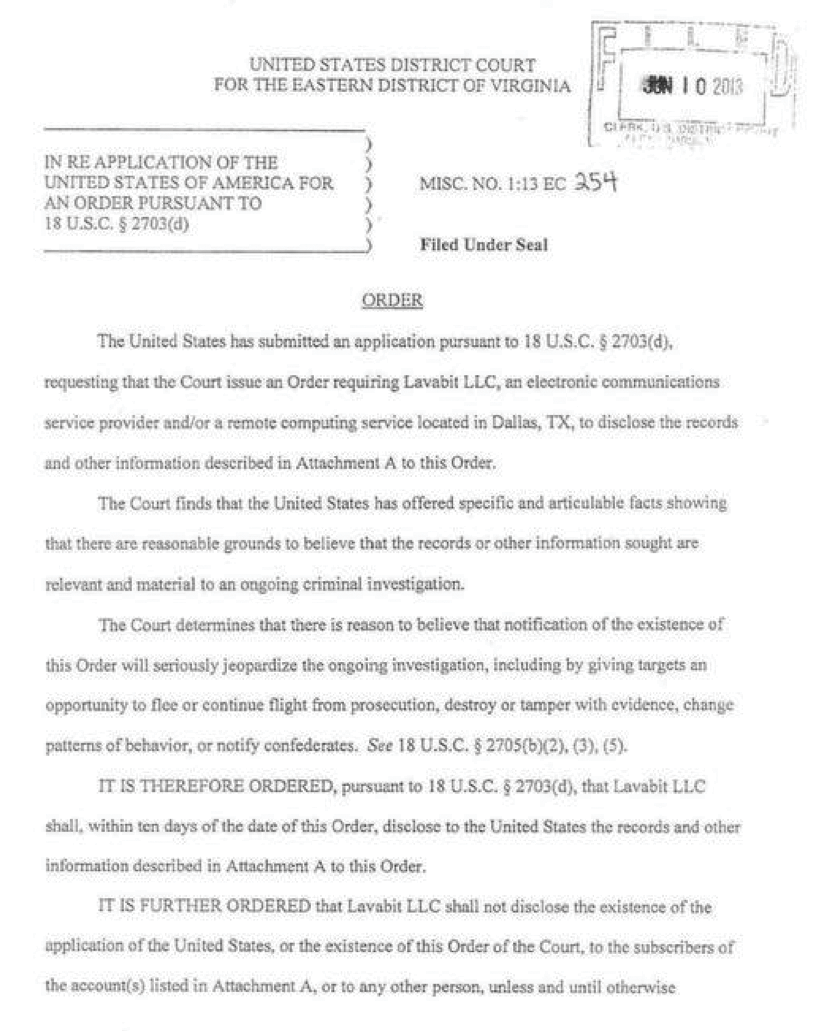

For a long time after its founding, Lavabit was simply one provider among many and didn't cause much of a stir. The company cooperated with the authorities as needed and probably would have remained just one mail provider among many, if it weren't for a certain customer with the email address edsnowden@lavabit.com (Figure 1). When Snowden first escaped abroad and began to disclose the most secret of secrets of the NSA, the fun was over very quickly for Lavabit, and the company saw itself facing various court orders (Figure 2) and search warrants.

![If Ed Snowden had not used Lavabit to send secure email, the service might still be around today. (CC BY 3.0 US [1]: Laura Poitras/Praxis Films, Wikimedia) If Ed Snowden had not used Lavabit to send secure email, the service might still be around today. (CC BY 3.0 US [1]: Laura Poitras/Praxis Films, Wikimedia)](images/F1_Edward_Snowden-2.png)

Investigators demanded that Lavabit hand over all the keys that had been used internally for customers. The authorities would effectively have been able to decrypt all the messages that Lavabit had ever forwarded. Lavabit initially tried to resist but soon abandoned its business model, not least because Ladar Levison would otherwise have ended up in jail (Figure 3).

Secure Email Ahead

Since then, Levison has become a man with a mission. Shortly after the demise of Lavabit, he made a public announcement that he intended to found a Lavabit successor. The successor would do no less than replace email with new technology and a design focused on security. Levison has put together a punch-packing team to do this, too (Figure 4) [2]:

![The famous names on the team behind Dark Mail (aka DIME) have a mission. (© 2014 Dark Mail Technical Alliance [2]) The famous names on the team behind Dark Mail (aka DIME) have a mission. (© 2014 Dark Mail Technical Alliance [2])](images/F4_team.png)

- Phil Zimmermann (Figure 5) [3] is the inventor of PGP and thus contributes much crypto knowledge as a pioneer of security in digital communications.

![Phil Zimmermann – shown on the right at the Open-Xchange Summit 2013 in Hamburg with Linux-Magazin editor Markus Feilner – is part of the DIME team and the inventor of PGP. (CC BY-SA 4.0 [4]: Markus Feilner) Phil Zimmermann – shown on the right at the Open-Xchange Summit 2013 in Hamburg with Linux-Magazin editor Markus Feilner – is part of the DIME team and the inventor of PGP. (CC BY-SA 4.0 [4]: Markus Feilner)](images/F5_MG_6845_web.png)

- Jon Callas can look back on a long career working on Internet security; he worked for DEC and PGP and was a founding member of Silent Circle [5], another secure mail communication service on the web based on the Lavabit principle.

- Mike Janke is the other co-founder of Silent Circle and a close friend of Jon Callas and Phil Zimmermann.

All told, the four prime movers backing this new project can offer a huge amount of experience in terms of encrypted communication, and they already have a name for their baby – or actually two: First, the new project goes by the name of Project Dark Mail. Levison collected many donations and much goodwill on Kickstarter [6] under this name. Recently the project was renamed DIME, which stands for Dark Internet Mail Environment. As you can see from this name, DIME is not looking to be just an email add-on for more security, which is the case with GnuPG.

The Whole Enchilada

DIME seeks to replace legacy email with a new service that works just like email but is fundamentally secure. This goal involves many points that are on the DIME project's agenda.

The most important factor for DIME in the eyes of its founders is end-to-end encryption capability, in which the lock and the key are only known to the two persons communicating. This is not just intended to cover the email content – DIME also seeks to encrypt all the metadata and thus ensure secure transmission. The only information that a fictional man-in-the-middle sees when Alice and Bob communicate is the length of the encrypted message. Additionally, the attacker only sees garbled data that is more or less impossible for even a megacomputer to crack.

This approach kills several birds with one stone. If DIME only provides the medium to the communication participants, but can't decrypt the information itself, law enforcement agencies can't exploit DIME to lever open the data safe. Comprehensive anonymization would mean that DIME would be unable to provide data, even if it wanted to. Additionally, because the digital keys are kept by the users, DIME itself has no chance whatsoever to syphon off payload data when dispatching messages. This would put DIME in the clear and provide the protection needed to avoid a repeat of the Silent Circle or Lavabit scenarios, both of which attracted the attention of law enforcement agencies.

Software, Services, Protocols, and Clients

DIME, however, is looking to take things a step further and publicize the software that it runs in the background. At the end of the day, DIME will be a service that administrators can operate on their own servers, as is the case with email today. In the course of their fundraising campaign, the developers stated this as their express objective: creating daemons for receiving and sending DIME messages on the basis of the software that ran at Lavabit.

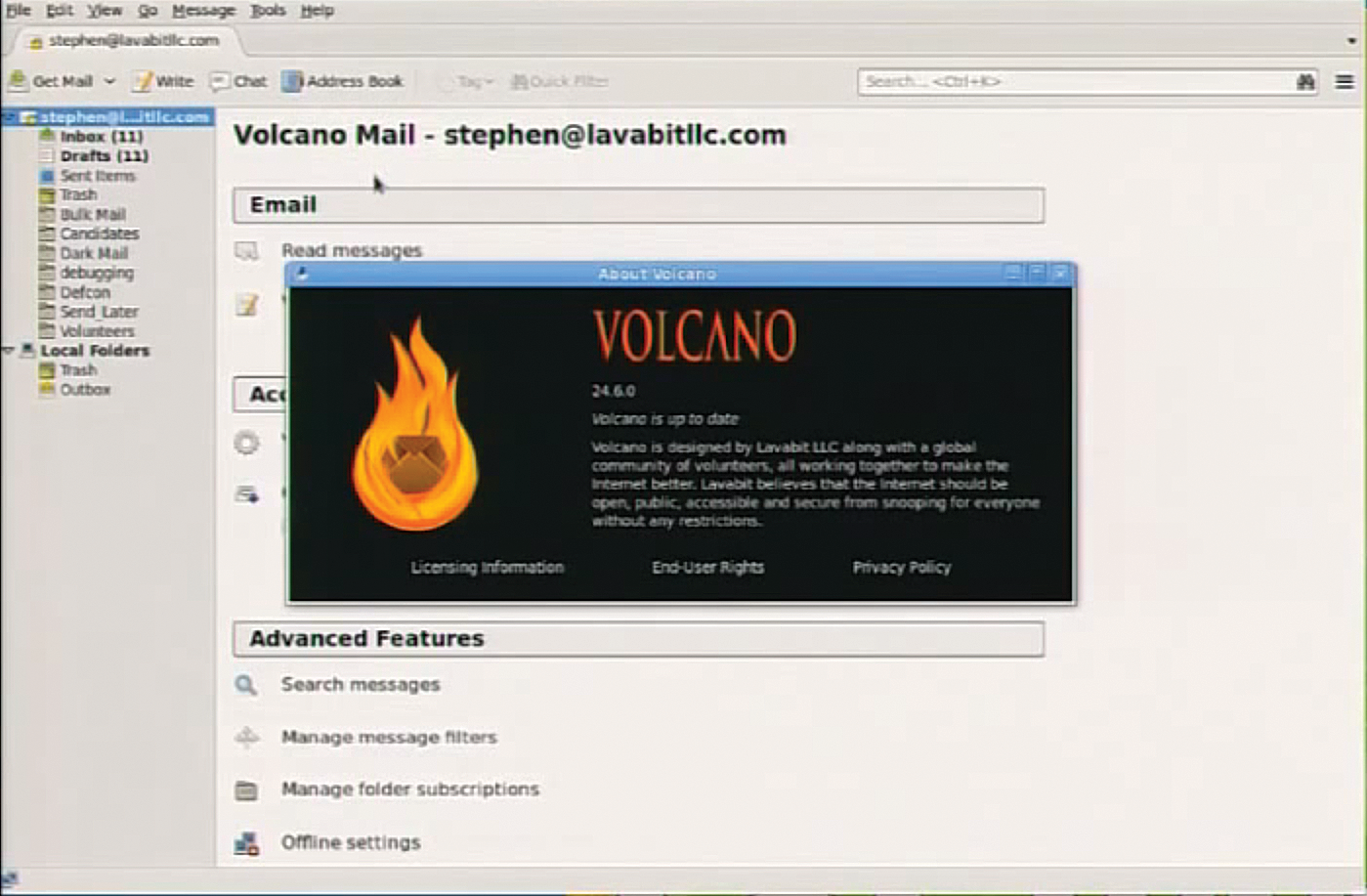

A protocol called DMAP is intended as a slot-in replacement for IMAP, but one that will work with DIME. In the meantime, the project has already shifted a fair distance away from its roots; many new features have been added to Lavabit components, and the other parts of the suite are already more than just good ideas. Levison himself presented the DIME client Volcano (Figure 6) at DEF CON 22 [7]; it is based on Thunderbird and shows some similarities, at least in terms of the user interface.

Trustful, Cautious, and Paranoid

Volcano gives users a choice of three operating modes, Trustful, Cautious, and Paranoid. Levison himself expressly points out that only Cautious and Paranoid modes can be regarded as secure. Only in these operating modes does DIME rely on end-to-end encryption, where the keys remain on the users' computers.

Speaking of keys: DIME will use an encryption that is similar to PGP for email. It also works with public keys, although DIME calls them signets. Users can then decide to trust each other's signets, which would be equivalent to signing a key in the PGP universe. This point of the story at least sounds a lot like GnuPG with all its weaknesses. Levison, however, solemnly promises that the inherent encryption in DIME will be far easier to use than ever was the case with GnuPG – specifically because it is part of the solution and not just an afterthought.

Anonymization Like Tor

The previously mentioned objective of encrypting the metadata is another obstacle, but one that DIME believes it has already worked around. After all, say the developers, a role model already exists for a network in which the two endpoints can communicate anonymously with one another without being monitored: Tor.

The makers of DIME, led by Levison, described DIME's transport mechanism as similar to Tor, meaning that various hosts are involved in the communications but never get to see the actual traffic. Like an onion, it is hidden under many layers. However, this approach actually causes a problem for DIME users wanting to communicate and exchange messages with non-DIME users. The only mode available to them in DIME is Trustful; additionally, Volcano expressly warns users about the lack of security before allowing a DIME user to send an unencrypted message to a normal email account.

Secure Key Distribution

Levison has been jetting around the globe recently and presenting his project at various conferences that focus on security. He also attended the Chaos Communication Congress in Berlin at the end of last year [8], where he talked about the motives behind his actions. In talking to Levison, one quickly gains the impression that the man knows what he's doing. This is evident in the details, which were often ignored in the use of GnuPG. As recently as December, for example, Richard Klafter and Eric Swanson conclusively demonstrated that 32-bit IDs for keys in GnuPG are quite easily predictable [9]. If you try, you can – in a very short time – generate a key set with thousands of keys that are mutually signed and have trustworthy-looking entries in the name and email fields. In other words, the procedure described here gives hackers the ability to generate keys whose IDs are identical to the IDs of "genuine" personalities. The problem doesn't affect the actual keys of those personalities; they are still as secure as ever.

The problem is that spoofed keys are only identifiable if users take the trouble to compare the fingerprints of the key that they know with the one that they use for encrypting a message. If they fail to do so, they are opening up the door to exploitation. This is all the more tragic when you consider that GnuPG has for years offered the option of using 64-bit key IDs. Virtually nobody uses this function, and very few GnuPG users are even aware of the problem or that a solution exists for it.

DIME has problems of this kind in its sights. Key distribution within the service will come with built-in security out of the box: The key servers used there will be sufficiently robust to prevent them being hijacked by malevolent services with a large budget. Additionally, the key management system will be integrated at such a low level in Dark Mail that users won't even notice it exists.

DIME Has Potential and Needs to Deliver

Not a lot of information is available on DIME. Conceivably, Levison and his partners do not want to expose DIME too much before it can actually do what it promises. Secret services like the NSA will no doubt view DIME as an insult and do everything they can to prevent the service from being used. DIME is obviously interested in not giving them an attack point for doing so. To damage DIME in its currently known design, such agencies would effectively have to prohibit encrypted communications across the board. This appears unlikely right now but not totally impossible; cryptography software was, for a long time, handled like a weapon in the United States and subjected to strict controls, especially when exporting it to foreign countries.

Some comprehensive testing will be needed to discover what DIME really can do after it goes live. If the developers succeed in successfully launching the service and publishing the required software as open source, the system could really take off. One thing is certain, though, legacy email has reached the end of the road in terms of IT security.