Working with the Exchange Management Shell

Strong Shell

Exchange Server has a customized version of PowerShell in the form of Exchange Management Shell (EMS). The extensions for the mail server are already loaded in the shell. The EMS is now clearly superior to the Exchange Management Console, and many administrative tasks are only possible via commandlets, which is a good reason to look more closely at PowerShell for Exchange.

Resistance is futile not only for Exchange administrators but also for managing SharePoint or Internet Information Services (IIS). Those who steer clear of the console do not have the options for performing all administrative tasks.

Microsoft has not necessarily followed a straightforward path regarding the implementation of PowerShell in Exchange Server since the 2007 version. After a brilliant beginning, Exchange Management Shell and Exchange Management Console were neck and neck in the 2010 version. An action such as activating an anti-spam agent on a hub transport server also created a corresponding management tab in the GUI.

Advantage: Shell

This equality no longer exists in Exchange Server 2013. The advanced settings of ActiveSync Policies have also been relocated. Permissions are now configured exclusively via the console. The options for granting individual rights using checkboxes no longer exist. Even rights such as the use of Internet Explorer or the camera can now only be set using parameters of the cmdlet Set-ActiveSyncPolicy.

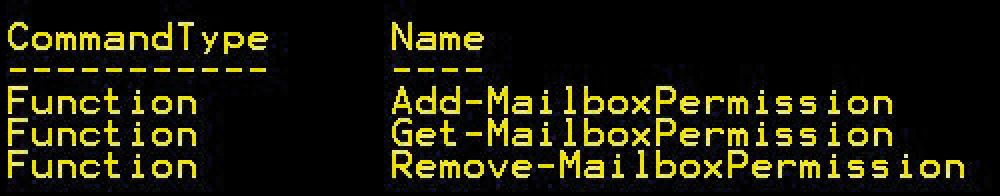

In this article, I will focus on mailbox permissions. PowerShell offers a script interpreter for PS1 files as well as a console. PowerShell processes command types called "monards" (function, alias, cmdlet) on this command level. These monards are grouped with command families, which are in turn shaped by common "nouns." Actions, the "verbs," are then allocated to each noun.

This principle becomes obvious if you consider the cmdlet Get-Mailbox. The command's target is a mailbox, the action is Get. The mailbox settings are represented by the noun MailboxPermission, which is logically located in User/Mailbox. If you enter the following command in PowerShell:

Get-<Command> -<noun> <MailboxPermission>

you will see the commands for mailbox permissions (Figure 1).

Managing Permissions

You can recognize the fundamental objective of the commands from the verbs:

-

Add: adds a new permission to a mailbox -

Get: shows the existing permissions. -

Remove: removes a rights entry.

You will always find at least one "get" associated with a noun. It is therefore always possible to retrieve the existing information for a managed object. I will list the existing permissions to get started. Unfortunately, it is not possible to do everything in one fell swoop as in:

Get-MailboxPermission

or

Get-MailBoxPermission -Identity *

The command Get-MailboxPermission absolutely requires the parameter -Identity <value>. In this case, <value> can assume the following information:

- GUID

- ADObjectID

- Distinguished name (DN)

- Domain|Account

- User principal name (UPN)

- LegacyExchangeDN

- SmtpAddress

- Alias

Transmitting a username would therefore be possible with:

Get-MailboxPermission -Identity office.onmicrosoft.com\office

You can qualify this list using the parameter -user to avoid unnecessary filter operations. By using the command:

Get-MailboxPermission -Identity office.onmicrosoft.com\office -user Tom

you can identify the permissions of user Tom for the corresponding mailbox.

In addition to the restriction on the rights holder, the switch parameter owner lets you focus on the right owner. This parameter does not expect a value but is instead set to False by default. If applied, only information about the owner is displayed. However, a combination with -user is not possible.

Return values are information about access rights (permissions). It is a complex object with attributes. The following functions are implemented:

-

Deny: deny yes/no -

InheritanceType: inheritance -

User,Identity -

IsInherited: inherited right yes/no -

IsValid,ObjectState: modification

As well as specifying the desired mailbox using the parameter -Identity, PowerShell provides you with much more flexible means for the query. The construct for this is the PowerShell pipeline. This allows you to transmit lists conveniently as InputObjects. The pipeline iterates over the values and binds them individually to the -Identity parameter. In the following example,

myfirst@mydom.com,mysecond@mydom.com, mythird@mydom.com | Get-MailboxPermissions

try replacing the corresponding sample values with valid mailboxes.

New Permissions Needed

If you want to set a new permission, use the Add-MailboxPermission command. Table 1 shows some parameters that you can use to control the command.

Tabelle 1: Parameters for the Target

|

Parameter |

Target |

|---|---|

|

|

Deny (yes/no) |

|

|

Mailbox, access to the target box is granted |

|

|

Owner of the target mailbox |

|

|

Account that receives a right |

|

|

Access rights as list |

To put this simply: The right or rights (AccessRights) are granted to the account user for the mailbox identity, which itself can again be a list. Next, I'll look at the rights types. One or more of the following access rights can be set:

ExternalAccountFullAccessDeleteItemReadPermissionChangePermissionChangeOwner

Everything is in place from assumption of ownership to full access. Values bound to the parameter AccessRights define the character of the right granted. Thus, if you want to give the user Tom read access to Jane's mailbox, you would invoke the following command:

Add-MailboxPermission -Identity jane -User tom -AccessRights ReadItems

If you want to change the ownership rights, use owner instead of user. It is not, of course, possible to use both parameters simultaneously. So, if Tom is to take over Jane's mailbox, you can do this using:

Add-MailboxPermission -Identity jane -Owner tom

If you want to change multiple mailboxes in your rights structure, use the pipeline. However, be careful: The pipeline operates very slowly. Large amounts of data are passed through the pipe individually, so processing does not take place in real time. The following command gives the user Tom full access to all mailboxes:

Get-Mailbox -ResultSize unlimited -Filter {(RecipientTypeDetails -eq 'UserMailbox')} | \

Add-MailboxPermission -User tom@mydom.com -AccessRights fullaccess -InheritanceType all

If you only want to control individual folders, use an extra cmdlet for this. You can apply the rights key a little more precisely to the mailbox folders using Add-MailboxFolderPermission. The parameters are almost identical, and the values transmitted are also of the same type:

Add-MailboxFolderPermission -Identity jane:\Sales -User tom -AccessRights Owner

Ownership of the mailbox folder Sales is now taken over by Tom. Revoking a right again follows the same path as an assignment:

Remove-MailboxPermission -identity jane -User tom -AccessRights full-access -InheritanceType all

Tom's full access to Jane's mailbox has been revoked. Inheritance is active, as in the example above.

Flexible and Reusable: Scripts

As powerful as the PowerShell commands are when creating or modifying mailbox permissions, they have one major drawback: Multiple use requires multiple input. One solution might be a script provided with parameters, and data containers could be text files, Excel spreadsheets, or databases.

In the example, a simple CSV file contains the values to be set in tabular form. The first line defines the keys separated by commas. On the basis of this first line, values are extracted dynamically from the CSV file, as in this example file:

identity,user,right,inheritance "Tom Meier",jerry@mydom.com,FullAccess,All Conferenceroom,tom,ReadItems,All [...]

The Import CSV cmdlet will then convert this file into a list of key-value pairs. You can now test for the path to your data source and, if successful, load all the data into the variable $ValuesField. If the file is not found, the application backs out with an exit code:

If (test-Path (PathtoCsvFile)){$ValuesField = import-csv PathtoCSVFile; }

Else {write-Host "Unfortunately the file was not found!" -foregroundColor "red"; Exit 1;}

Then, you can evaluate the exit code with the use of the $LastExitCode variable. Now you need a few test routines that test the validity of the data stored in the file:

Function validateUser ($ExObj){

If (Get-user -Identity $ExObj -EA SilentlyContinue) {

Return $TRUE;}

Else {Return $FALSE}}

Listing 1 then starts processing each line in the CSV file.

Listing 1: Processing the CSV File

Foreach ($line in $valuesfield){

$PosIdentity = $line.identity;

$PosUser = $line.user;

$PosRight = $line.right;

$PosInheritance=$line.inheritance;

If (-NOT(validate $PosIdentity){"$PosIdentity was not found!";Exit 2}

ElseIf {(-NOT(validate $PosUser){"$PosUser was not found!";Exit 3}

Else{

$ErrorActionPreference="stop";

#Dynamic change begins

trap {"Error in the allocation. `n let's try the other changes";continue}

Add-MailboxPermission -Identity $PosIdentity -User $PosUser -AccessRights $Posright -Inheritance $PosInheritance;

}

Error handling is implemented in the scope of the loop. If an error occurs when processing because of missing permissions, output is generated and the next line is evaluated. To make this script more dynamic, I recommend transmitting the CSV file by means of a parameter.

Conclusions

PowerShell is increasingly the method of choice for managing Exchange Server. The scripting language demonstrates its strengths as a flexible tool, particularly for mass changes. You will find scripts based on it for repetitions and variable actions. Once you have familiarized yourself with the necessary cmdlets, and created a number of scripts for frequent use cases, Exchange management should be easy.