Countering embedded malware attacks

The Return of the Macro Virus

Embedded malware hidden as macros in Office documents, which automatically launch on opening, was extremely popular 15 years ago. To counter this, in 2001, Microsoft introduced a security policy in Office XP that prompted the user to decide whether or not to run code embedded in documents. This made macro virus attacks difficult to perform, so that other propagation paths became far more lucrative. Consequently, in the last few years, this form of malicious code has been almost completely forgotten, not least because manufacturers by default disabled macros in their products.

However, a Microsoft study from early 2015 shows evidence of a return of the macro virus. According to reports, within a very short time, more than 500,000 systems were infected by malware distributed in email spam. Today, macro viruses are again on the rise.

Hidden in Office Files

A macro virus is a piece of malicious code that exists as a standalone executable program but is embedded as a macro in a document. A macro can perform certain tasks automatically; it is used to perform malicious actions, such as installing more malicious code. Files that contain a macro virus and distributed via email are usually designed so that they appear inconspicuous to the receiver. Most users typically open invoices, reminders, and application documents without much thought.

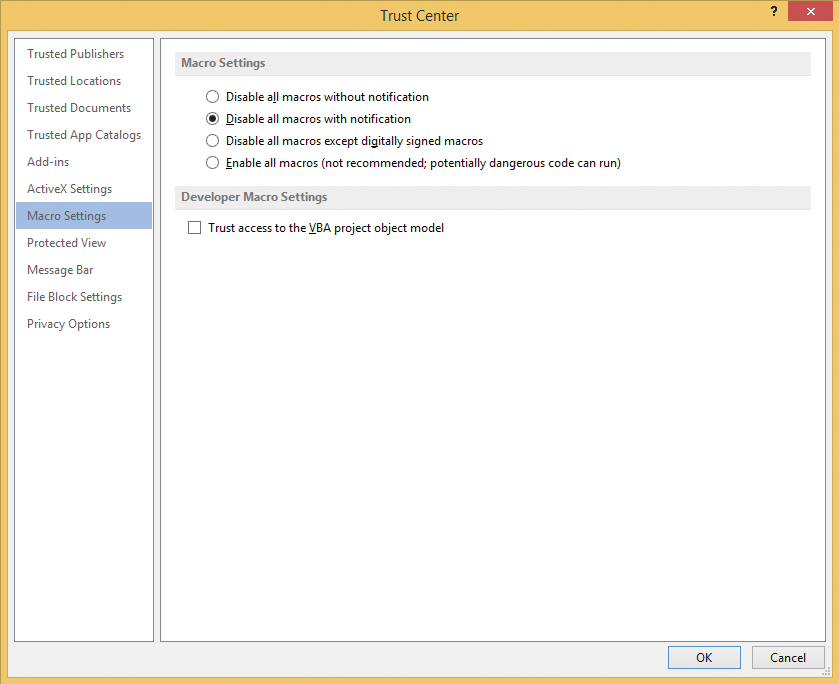

Because macros are now disabled by default (Figure 1), many of these malicious files now contain step-by-step instructions for enabling macros. By suggesting that they would otherwise be unable to open and read the document, the recipient is thus lured into allowing the execution of macros. Additionally, targeted social engineering is used to pique the interest of the victims, and targeted attacks are performed on large groups of people and companies – often using file names such as BoardPayroll.xlsx or ConferenceAgenda.xlsx. Today, macro attacks rely on new tools and techniques, such as packed file formats and cloud services like Dropbox, to bypass anti-spam and antivirus scanners.

Dridex

Dridex, which is known banking trojan malware, has recently used a new attack vector. The trojan is used to steal money from companies in the United States and Europe by means of sophisticated attack methods. In Belgium, 35,000 clients who used the same banking solution were attacked. Using a large spam campaign, the attacker sent email to the sales departments of companies notifying the recipients that a new contract had been awarded; the email contained a fake invoice in Microsoft Office format.

The attachment with the DOC file name fooled people into thinking it was a harmless Word file. In fact, it was a MHTML file, a popular archive format for web pages. Microsoft Word supports the format as MHT files. Assumedly, the attacker simply renamed the file name extension to DOC to simulate a common file type that is usually opened by unsuspecting users without any concerns. Unfortunately, MHT and DOC files use the same icon, thus making it even more difficult for users to notice a difference.

The document contains a macro that enables malicious code downloads and thus acts as a downloader. In this case, the malicious code was hosted on a legitimate website, pastebin.com, a free web application that allows you to store and share text (including source code) with others for a set time period. Typically, these services are not blocked through blacklisting for company employees.

The attackers used pastebin.com to host a hidden Visual Basic Script (VBS), which installed and then executed o8237423.exe in %APPDATA%. The EXE file is a downloader that attempts to achieve administrative privileges by bypassing user account control (UAC) before actually loading the malicious software. Once this is achieved, the payload is downloaded from a web server.

Recommendations

The email security infrastructure is the first major hurdle for the attacker. It is therefore advisable to make sure that multistage scans (ideally products by several manufacturers) and advanced heuristic, behavioral, and reputation checks take place. Because this often can only be implemented at a significant cost for small or medium-sized businesses, you might want to consider a security-as-a-service approach, where applicable.

If possible, switch off all script interfaces via Group Policy. Ensure that all products, such as Microsoft Windows and Office, as well as all third-party applications, are always patched to the current security levels. Also, you should use appropriate endpoint security that performs heuristic, behavioral, and reputation checks in addition to standard testing and scanning tasks. This ensures that all harmful files that have been detected elsewhere on the Internet are automatically blocked.

Probably the easiest and the most effective measure is raising staff awareness. Train your staff regularly and inform them proactively of the latest attack methods. In the case of macro malware, the basic statement should be "never enable macros."

Conclusions

Rapid development of macro viruses, such as Dridex, accompanied by sophisticated workaround techniques, highlight the risk potential. Traditional signature-based protection mechanisms are no longer fully effective and can be worked around by attackers using relatively simple means. An increasingly growing range of attack vectors necessitates new countermeasures.