Keeping Docker containers safe

Weak Link

Few debate that the destiny of a hosting infrastructure is running applications across multiple containers. Containers are a genuinely fantastic, highly performant technology ideal for deploying software updates to applications. Whether you're working in an enterprise with a number of critical microservices, tightly coupled with a pipeline that continuously deploys your latest software, or you're running a single LEMP (Linux, Nginx, MySQL, PHP) website that sometimes needs to scale up for busy periods, containers can provide with relative ease the software dependencies you need across all stages of your development life cycle.

Containers are far from being a new addition to server hosting. I was using Linux containers (OpenVZ) in production in 2009 and automatically backing up container images of around 250MB to Amazon's S3 storage very effectively. A number of successful container technologies have been used extensively in the past, including LXC, Solaris Zones, and FreeBSD jails, to name but a few.

Suffice to say, however, that the brand currently synonymous with container technology is the venerable Docker. Vendors, embracing their ever-evolving technology, in hand with clever, targeted marketing and some very nifty networking improvements, have driven Docker to the forefront of techies' minds and helped Docker ride on the crest of the DevOps wave. Docker provides businesses at all levels the ability to approach their infrastructure from a different perspective and, along with other DevOps technology offerings, has genuinely twisted the old paradigm and rapidly become the new norm.

As more businesses adopt such technologies, however, teething problems are inevitable. In the case of Docker, the more you use it, the more concerned you become about secure deployment. Although Docker's underlying security is problematic (great strides have been made to improve it over time), users tend to treat containers as though they are virtual machines (VMs), which they most certainly are not.

To begin, I'll fill you with fear. If I communicate the security issues correctly, you might never want to go near a container again. I want to state explicitly at this stage that these issues do not just affect the Docker model; however, because Docker is undoubtedly the current popular choice for containerization, I'll use Docker as the main example.

To provide sanity toward the end of the article, I offer some potential solutions to mitigate the security issues that you might not have considered to affect your containers previously.

Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt

As I've alluded to already, a number of attack vectors exist on a system that runs a Docker daemon, but to my mind, the most critical is the Docker run command and a handful of other powerful commands.

The run command is powerful because it runs as the root user and can download images and mount volumes, among other things. Why is this bad? Well, the run command can legitimately mount the entire filesystem on the host machine with ease. Consider being able to write to any file or directory from the top level of your main disk with this command, which mounts a volume using -v:

$ docker run -v /:/tmp/container-filesystem chrisbinnie/my-web-server

Inside the container's filesystem (under the directory /tmp/container--filesystem), you can see the whole drive for the host system and affect it with root user access.

As simply as I can put it, should you give access to common Docker commands to any user or process on your system, then they effectively, without any other rules being enforced, have superuser access to your entire host machine and not just the container that they're running.

The Docker website [1] doesn't hold back in telling users to exercise caution with their Docker daemon:

Running containers (and applications) with Docker implies running the Docker daemon. This daemon currently requires root privileges, and you should therefore be aware of some important details.

First of all, only trusted users should be allowed to control your Docker daemon. This is a direct consequence of some powerful Docker features. Specifically, Docker allows you to share a directory between the Docker host and a guest container; and it allows you to do so without limiting the access rights of the container. This means that you can start a container where the /host directory will be the / directory on your host; and the container will be able to alter your host filesystem without any restriction. This is similar to how virtualization systems allow filesystem resource sharing. Nothing prevents you from sharing your root filesystem (or even your root block device) with a virtual machine.

Now that I've given you cause for alarm, let me elaborate. First, I'll explore the key differences between VMs and containers. I'm going to refer to a Dan Walsh article [2]; Walsh does work for Red Hat and was pivotal in the creation of the top-notch security tool SELinux [3]. As the joke goes, Walsh weeps when you switch off SELinux and disables its sophisticated security because you don't know how to configure it [4].

Permit me to paraphrase some of the content from Walsh's aforementioned article as I understand it. Before continuing, here's a super-quick reminder about device nodes, which Linux uses to speak to almost everything on a system. This is thanks to the sophisticated tool that is Unix, which brought us Everything Is A File [5]. For example, on your filesystem, a CD-ROM drive in Linux is usually a file called /dev/cdrom (actually, it's a symlink to /dev/sr0 for a SCSI drive), which streams data from your hardware to the system.

For security reasons, when a hypervisor helps run a system, the device nodes can talk to the VM's kernel but not the host's kernel. As a result, if you want to attack the host that is running on a VM, you first need to get a process to negotiate the VM's kernel successfully and then find a vulnerability in the hypervisor. After those two challenges have been met, if you're running SELinux, an attacker still has to circumvent the SELinux controls (which are normally locked down on a VM) before finally attacking the host's kernel.

Unfortunately for those users running containers of the popular variety, an attacker has already reached the point of talking to the host's kernel. In other words, very little protective buffering lies between taking control of a container and controlling the whole host running the container's daemon.

Therefore, by giving a low-level user access to the Docker daemon, you cannot break an established security model (sometimes called the "principle of least privilege" [6]), which has been used since the early 1970s: Where normal users may run certain commands, admin users may run a few more commands with slightly more risk associated with them, and superusers can run any command on the system. To reinforce the matter at hand, Figure 1 explains the official word from Oracle on giving access to the Docker command.

![Oracle's warning about Docker command access [7]. Oracle's warning about Docker command access [7].](images/F01.png)

Well-Intentioned Butlers

At this juncture, let me use the popular automation tool Jenkins [8] as an example, because it's highly likely that Jenkins is being used somewhere on a continuous integration (CI) pipeline near you to run automated jobs. Likely, one or more of these Jenkins jobs affect Docker containers in some way by stopping, starting, deleting, or creating them.

As you might guess, any privileged job (e.g., running a container) would need direct access to the Docker daemon. Even when you follow documentation and set up a Docker system group (e.g., the docker group), you're sadly not protected and are effectively giving up root access to your host. Being a member of the docker system group means that a human, process, or CI tool such as Jenkins can use SSH keys or passwords to log in to a host running the Docker daemon and act like the root user without actually being the superuser.

Ultimately this means your Jenkins user (or equally any other user or process accessing your Docker daemon) has full control of your host, so how your Jenkins logs in and authenticates then becomes a superuser-level problem to solve.

From a security perspective that's bad news. Imagine silently losing a host in a cluster, with an attacker sitting quietly for a month or two picking up all your data and activity for that period before exposing their presence – if they ever do. Such attacks of the Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) variety are more common than you might think.

Privilege Separation

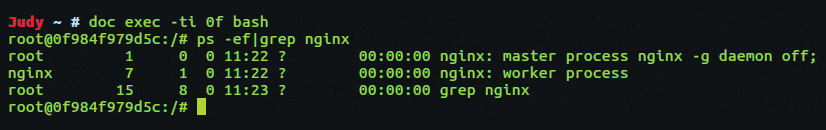

A quick reminder about privilege separation and why it's so important before continuing: An application like Nginx, the lightning-fast web server, might start up as the root user so that it can open a privileged port within the TCP 0-1024 port range. By default, these ports are protected from all but the root user to stop the nefarious serving of data from common server ports.

In the case of a web server, of course, the most common ports would usually be TCP ports 80 and 443. Once Nginx has opened these ports, worker processes run as less privileged users (e.g., user nginx) in an attempt to mitigate any exploits on the Nginx daemon running as the root user.

As a result, your network-exposed ports don't have your root user sitting attentively waiting for an attack; instead, a user with much less system access listens. You can find out more about privilege separation online if you're interested [9].

In Figure 2, you can see which user the Docker container is exposing to the big, bad Internet at large. Thankfully, it's not the root user but the nginx user, as it should be.

Contain Your Surprise

Host security, however, is only half the battle. Now, consider the fractionally less complex containers themselves. I say that securing the containers is less complex because one trick can reduce a container's attack vectors significantly – that is, running a container using the --read--only option:

$ docker run -d --read-only chrisbinnie/my-web-server

As you might expect, this launches a container to which you cannot write in any way, shape, or form. In other words, if your container is attacked, the attacker can't write to the application. This is not always a popular way to use containers, although it's recognized as a quick and highly effective way of reducing their risk to other containers on a system and the host machine itself.

The effect of making a container read-only means, among other things, that when the container is stopped and restarted, the hack needs to take place all over again to be effective and can't be written into your application automatically. I think of these containers as Knoppix-style boot disks or ROM (Read-Only Memory) [10].

Consider that even opening a page in a web browser needs to write session data to your desktop machine. If you make a container read-only, then although you can read all the data you want from a container's processes, you need to provide other ways of writing data. You might try and save to the host itself, but a better method would likely be to write to a permanent or temporary storage device, depending on the type of data you're dealing with. For example, ephemeral session data is thrown away most of the time, but storing input from a user into an application that isn't written to a database might suit Amazon S3 [11] or sophisticated, redundant, off-host storage like Ceph like Ceph or the more cloud-friendly GlusterFS [12].

It's What's Inside that Counts

Security used to be much worse when it came to the internals of a container. Up until Docker v1.10, a host's root user also tied to the container's root user, which could cause all sorts of chaos, such as being able to load a kernel module dynamically into the kernel and do any damage to the host machine that you want. Thankfully, Docker has addressed this issue skillfully, but getting it to work requires overhead. The official line [13] from the Docker site is:

As of Docker 1.10 User Namespaces are supported directly by the docker daemon. This feature allows for the root user in a container to be mapped to a non uid-0 user outside the container, which can help to mitigate the risks of container breakout. This facility is available but not enabled by default.

It's highly recommended that you enable this functionality along with that of running "untouchable" containers that are read-only. A blog post [14] has information on how to map the root user's UID 0 to another UID and discusses how each tenant on a host can run their own range of UID and GID values without overlapping into the territories of others, thus causing other security concerns.

Mitigation Techniques

Moving away from doom and gloom, I'll now spend some time looking at how you can improve your security on Docker hosts and containers alike. You might be surprised at the number of additions you need to make to your Docker config to mitigate the many types of attacks. I will continue by touching on a few of them briefly to give you food for thought, in the hope that you can investigate further, because the list is extensive and a little daunting, especially when written in detail.

- Improve your host and container logging (e.g., with a centralized, alerting Syslog server).

- Run through the Center For Internet Security (CIS) hardening document for your daemon [15].

- Run Docker on a host by itself, and don't introduce further issues with other on-host applications; in other words, keep a stripped-down, minimal install of all other packages on the host.

- Run your Docker daemon from a Unix socket, as recommended in modern versions.

- Re-map your root UID, despite the sometimes time-consuming overhead.

- Lean on the

--read-onlyoption, and don't let anyone tell you otherwise; store your data off-host. - Never run privileged containers unless in development, because they give unmitigated root user access on the host itself by design.

- Limit CPU usage per container and define maximum RAM usage to limit attacks on a container affecting others.

- Use SELinux, if possible; otherwise, use AppArmor [16], grsecurity [17], or PaX [18] to lock down unexpected system resource access.

- Patch your systems more often than usual; even official Docker images can be riddled with known vulnerabilities.

- Don't run containers with

cap-add=ALL; instead, shut all extended container capabilities down and then explicitly open them up. Listing 1 shows how to switch everything off and explicitly allow host access to a container to limit the host's exposure to exploits on the container. Table 1 lists capabilities that are not included by Docker by default but that can be enabled, and Table 2 lists capabilities that are enabled by default but that can be disabled [19]. - Limit container-to-container communications by using

--icc=false. - Check your configuration with the extensible Docker Bench for Security tool [20].

Tabelle 1: Capabilities Not Included by Default

|

Capability Key |

Capability Description |

|---|---|

|

|

Load and unload kernel modules. |

|

|

Perform I/O port operations ( |

|

|

Use |

|

|

Perform a range of system administration operations. |

|

|

Raise the process nice value ( |

|

|

Override resource limits. |

|

|

Set system clock ( |

|

|

Use |

|

|

Enable and disable kernel auditing; change auditing filter rules; retrieve auditing status and filtering rules. |

|

|

Allow MAC configuration or state changes. Implemented for the Smack Linux Security Module (LSM). |

|

|

Override Mandatory Access Control (MAC). Implemented for the Smack LSM. |

|

|

Perform various network-related operations. |

|

|

Perform privileged |

|

|

Bypass file read permission checks and directory read and execute permission checks. |

|

|

Set the |

|

|

Make socket broadcasts and listen to multicasts. |

|

|

Lock memory ( |

|

|

Bypass permission checks for operations on System V IPC objects. |

|

|

Trace arbitrary processes using |

|

|

Use |

|

|

Establish leases on arbitrary files (see |

|

|

Trigger something that will wake up the system. |

|

|

Employ features that can block system suspend. |

Tabelle 2: Capabilities Enabled by Default

|

Capability Key |

Capability Description |

|---|---|

|

|

Modify process capabilities. |

|

|

Create special files using |

|

|

Write records to kernel auditing log. |

|

|

Make arbitrary changes to file UIDs and GIDs (see |

|

|

Use RAW and PACKET sockets. |

|

|

Bypass file read, write, and execute permission checks. |

|

|

Bypass permission checks on operations that normally require the file system UID of the process to match the UID of the file. |

|

|

Don't clear set-user-ID and set-group-ID permission bits when a file is modified. |

|

|

Bypass permission checks for sending signals. |

|

|

Make arbitrary manipulations of process GIDs and supplementary GID list. |

|

|

Make arbitrary manipulations of process UIDs. |

|

|

Bind a socket to Internet domain privileged ports (port numbers <1024). |

|

|

Use |

|

|

Set file capabilities. |

Listing 1: Shutting down container capabilities

$ docker run -d --cap-drop=CHOWN --cap-drop=DAC_OVERRIDE --cap-drop=FSETID --cap-drop=FOWNER --cap-drop=KILL --cap-drop=MKNOD --cap-drop=NET_RAW --cap-drop=SETGID --cap-drop=SETUID --cap-drop=SETFCAP --cap-drop=SETPCAP --cap-drop=NET_BIND_SERVICE --cap-drop=SYS_CHROOT --cap-drop=AUDIT_WRITE chrisbinnie/my-web-server

A Whole Host of Changes

Although I've run through a number of ways to harden your Docker daemon and containers, there are still issues presented by the not-so-helpful butler, Jenkins. When you add more security to any solution, there's always an overhead akin to adding PINs to your credit cards or another lock to your front door (so you have to carry another key and replace it when it's been lost). As far I've discovered so far, though, there's really only one type of solution to the problem of root user access being made available to the Docker daemon.

That solution is adding (potentially) lots of granular rules to each user or adding another type of user or process to intercept the commands being run. With this approach, you limit who can run what, mount what, download what, and so on. Initially, the overhead might be a little tiresome, but ultimately this solution offers a finely tuned level of access on each host.

One freely available way to create such rules is AuthZ from a pioneering company called Twistlock [21]. Their GitHub page spells out the basic policy enforcement [22]. The impressive Twistlock also has a commercial product that includes several additional eye-watering features, such as scanning containers for Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVEs) in an efficient manner through a friendly web interface. Importantly, they also manage to remove the need to write lots of rules manually using sophisticated machine learning. Additionally, there's a free-to-try Developer's Edition that's sophisticated and brimming with useful features [23] and a useful whitepaper.

Rocket-Fueled Containers

A direct rival to Docker is the CoreOS product rkt (pronounced rock-it). CoreOS sells rkt [24] out of the box as "a security-minded, standards-based container engine." You might have heard of CoreOS, because they also produce etcd and flannel, which are used by OpenShift and Kubernetes, the container orchestration engines. You can find plenty of interesting security information on the CoreOS site.

I have only used rkt for testing but have been genuinely intrigued with how I might best use it in an enterprise environment. It is slick, performant, and – would you believe – Docker container-compatible. You might be able to tell that I'm a fan. Be warned, however, that its maturity could potentially cause stumbling blocks. There's more information on migrating between Docker and rkt online [25].

I mention rkt because it boosts host security by introducing a local hypervisor into the mix – KVM [26] in this example:

$ rkt run --insecure-options=image --stage1-name=coreos.com/rkt/stage1-kvm:1.21.0 docker://registry-1.docker.io/library/nginx:latest

The turbo-charged rkt uses a KVM plugin of sorts and announces that it's using an "insecure" (unsigned) image to launch a docker://-built image. The docs for this can be found online [27].

I will leave you to come to grips with how the clever isolation works, but the handy diagram in Figure 3 explains which component is used with the KVM approach and how it compares to the usual systemd method. I have read that similar functionality will be available via pluggables in Docker when it moves to using containerd [29] as its run time in a future version.

![The components used when container and KVM methods are used to launch a container in rkt [28]. The components used when container and KVM methods are used to launch a container in rkt [28].](images/F03_NEW.png)

Horses for Courses

Which container solution suits your needs? The quick answer is that you have a whole host of options (pun intended), and you probably will not find a one-size-fits-all solution.

For more in-depth reading, you can spend a few minutes reading a comparison of current container technologies [30] on the CoreOS site, which could be biased, intentionally or not.

You have your work cut out securing containers. I hope the methods I've suggested for mitigating their security issues offers you some solace. Before you relax too much, however, you should read a somewhat scathing but informative blog post about the dangers of the docker group [31]. Comments such as "broken-by-design feature" are certainly a reminder to stay vigilant.