Putting an Active Directory domain controller in the Azure cloud

Cloud Director

Since Azure 2010 achieved production maturity, much has happened on Microsoft's cloud platform. Continuous innovations see the service rapidly growing, and administrators can choose from a variety of goodies from the Microsoft portfolio of new technologies. What looks so simple at first glance can turn out to be tricky when it comes to the details.

One popular option is to integrate cloud resources with existing infrastructure in a hybrid configuration. A hybrid network lets you keep your most essential core resources close and local, while still enjoying the benefits of a cloud for scaling to meet demand.

Once you get a significant part of your network up in the cloud, you might be wondering if you can put an Active Directory domain controller in the cloud also to facilitate authentication for cloud resources and act as a backup for local domain controllers (DCs).

This article shows how to get started with adding a domain controller to your Azure configuration.

Confusion with Portals

Azure offers two management portals: the classic model and the resource-based model [1]. The older model is the classic deployment model. Certain activities, such as Azure Active Directory, can only be managed from the classic model. The model for the resource manager has been around since 2014, and it was long dubbed the "Preview Portal." Since last year, according to Microsoft, the resource manager portal is now the preferred portal.

Of course, the services acquired for a subscription can extend across both models (portals); however, mixing the models makes management more difficult, because you won't be able to manage everything through a single interface.

Servers in the Cloud

Virtual servers are likely to be one of the most widely used technologies in Azure. There are many possible ways to deploy them, either through one of the portals or PowerShell or by using the cross-platform command-line interface for Windows, Linux, and OS X.

You can select an image from the predefined catalog. Some images feature an application, such as SQL or SharePoint. You can expand the catalog of available images with your own creations and launch new servers based on your personal images, prepared with Sysprep, then upload these images as VHD files to Azure [2].

Pay attention to what you call the components you add to your cloud network. As your network grows, you'll find it much easier to navigate if you use a naming convention that gives a shorthand description of the resource. See the box titled "Naming Conventions" for more on naming servers and other resources in Azure.

Extend On-Premises AD toward Azure

Suppose you want to extend your local Active Directory (AD) to work with Azure. The target is an AD site that is based on a subnet in Azure – along with a DC in Azure, provided by a local VM. Keeping a domain controller in the cloud allows your cloud-based servers to authenticate without having to take a long detour across the WAN. Also, if the DC in the local data center even goes down, the Azure DCs can still authenticate via the site topology.

Interestingly enough, setting up an AD site in Azure by placing your own DCs there has nothing to do with Azure Active Directory (AAD). AAD is a separate service that holds identities for Office 365 and gives the administrators in Azure roles and rights for Azure work. The scenario presented in this article is not concerned with AAD but with creating a replica of the local AD in Azure.

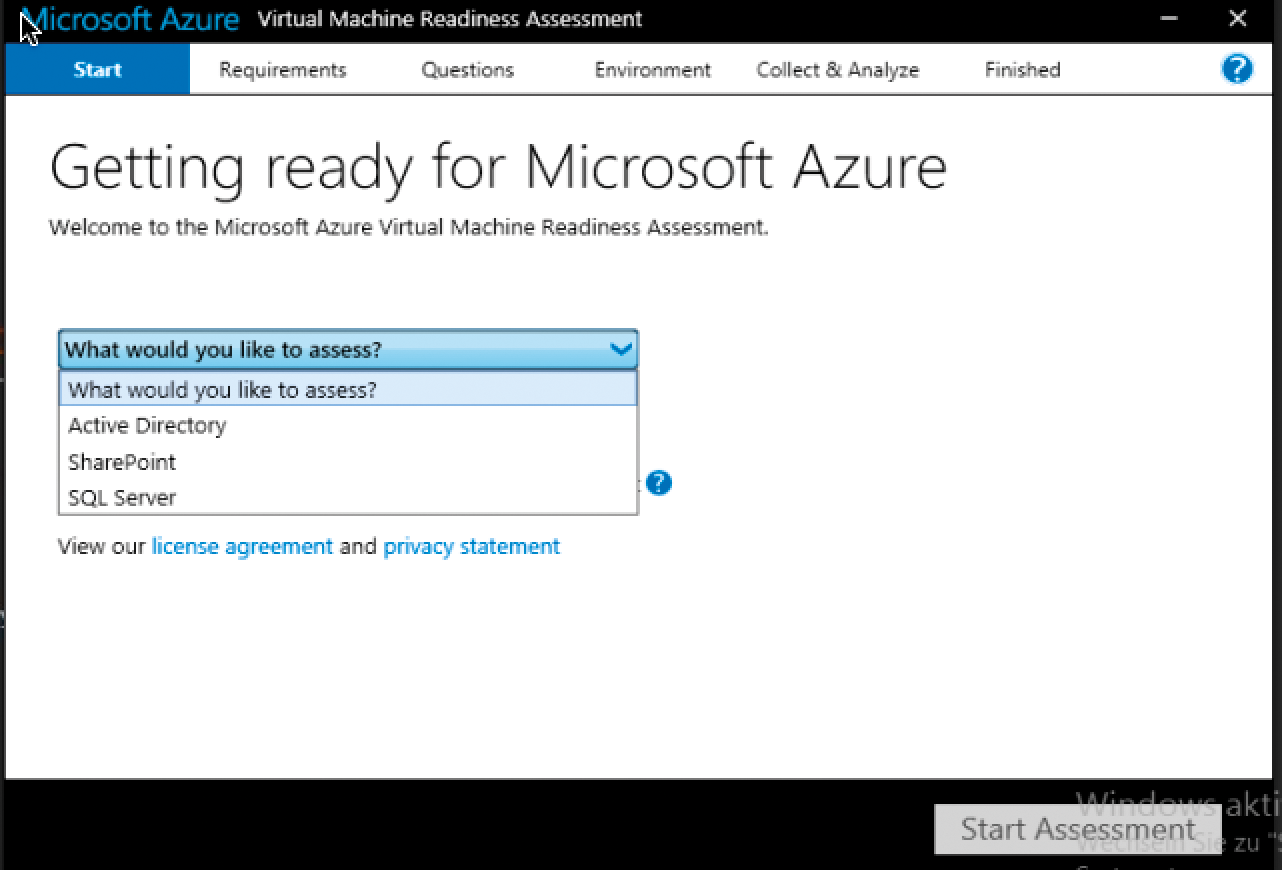

First, you need to check out your AD and decide whether your environment is suitable for the extension to Azure. This is what the "Virtual Machine Readiness Assessment Test" [4] does; you need to answer a couple of questions at the beginning (Figure 1). Armed with the information you provide, the tool checks to see whether the local scenario matches your plans. Among other things, the assessment test examines the network connection and tests the health of the domain controller using dcdiag (Domain Controller Diagnosis). The test is also suitable for a SQL or SharePoint setup. The result of the test is summarized in a Word file, which also provides links to further information.

Connecting Networks

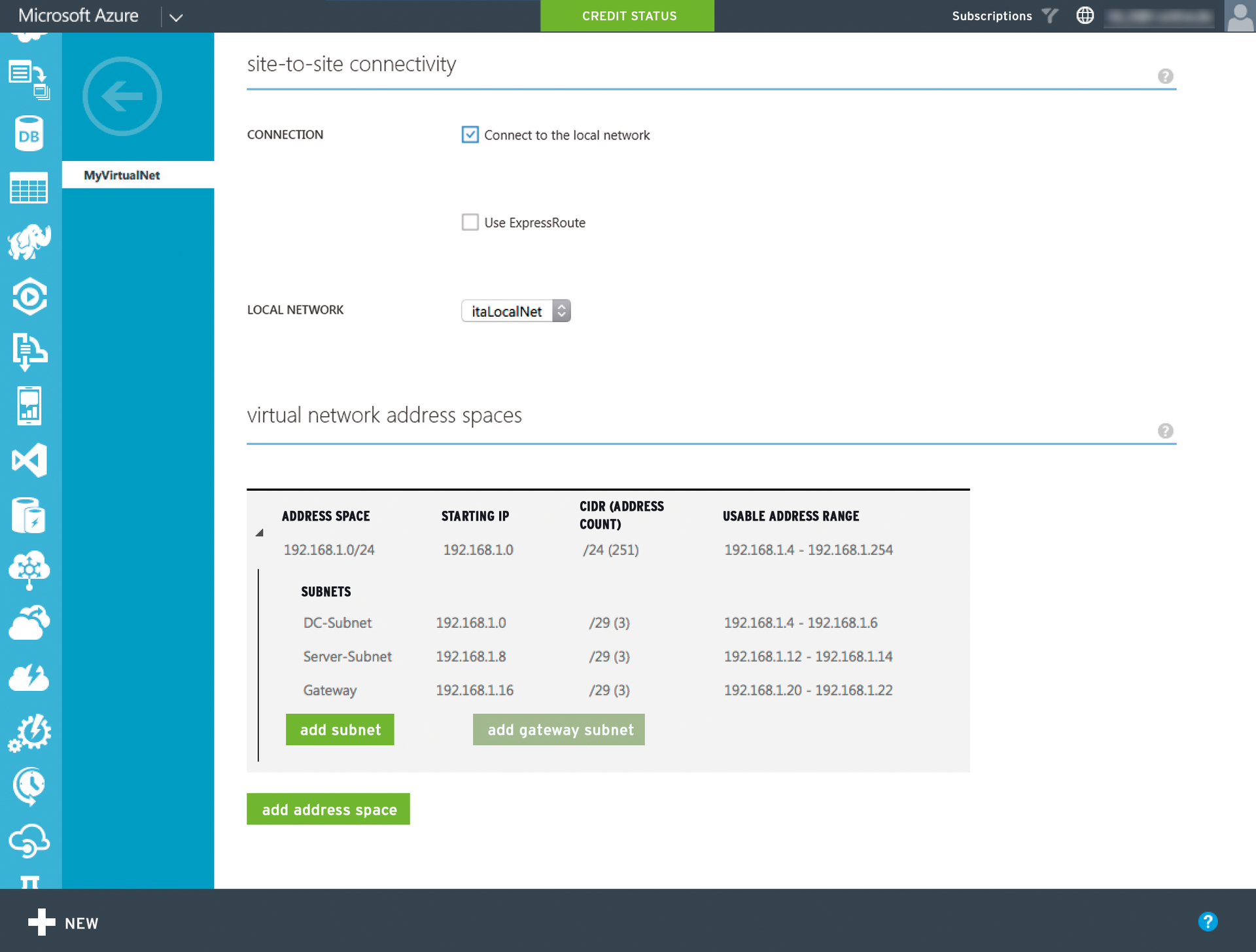

Assuming everything is in order, you need to lay the foundation to connect your local network with the Azure network. To do this, you set up a site-to-site VPN that you configure on both the local network and in Azure. In Azure, this configuration involves three steps: First, you set up a local area network. This network includes, as the name implies, the on-premises IP address space plus a public IP address for the VPN gateway. You then register a DNS server from the local AD, which will later be used by the VMs in Azure. Finally, you create the virtual network, consisting of the appropriate subnets.

In Azure, all three settings for this procedure are available in the classic portal in the Networks section of the left navigation bar. The configuration of the DNS servers and the local network is self-explanatory. During the configuration of the virtual network, select the previously created local network and the DNS server you added. Figure 2 shows the settings of the subnets used to create the virtual network. What is not shown is the dynamic gateway, which is activated via the same link (located at the bottom of the dashboard for the virtual network) with a single click.

You do not need certificates, by the way. Certificates are only necessary for a point-to-site VPN. In this example, Azure uses a shared secret for the connection with the remote access server. After completing all three steps in Azure, continue with the settings on your local network.

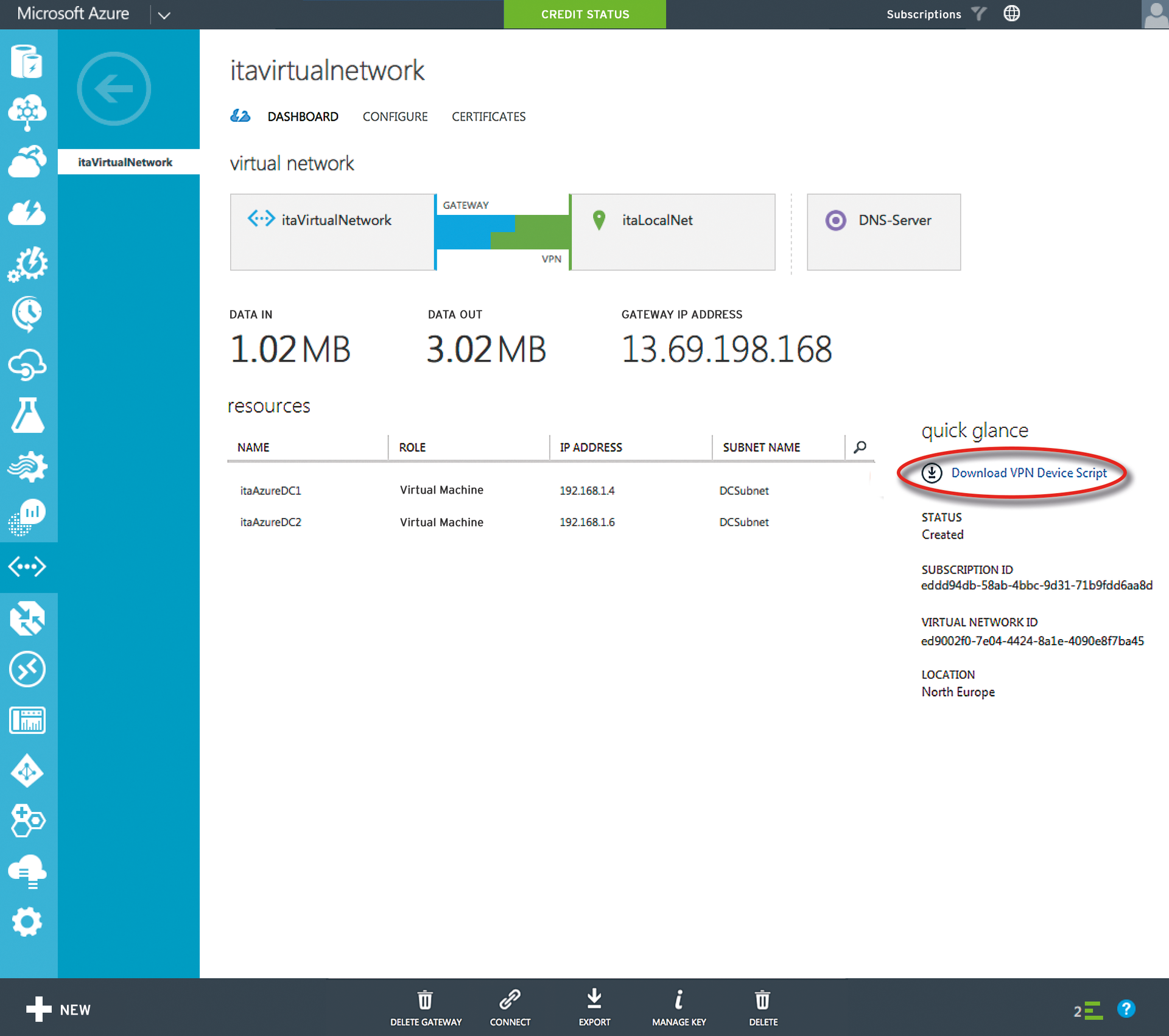

A pre-built script helps to configure the VPN device on the local network; Azure generates this script based on network information you furnished. You will find the script in the dashboard of the newly created virtual network by following the Download VPN Device Script link (Figure 3). Azure supports various network equipment manufacturers, including Juniper and Cisco.

As an example, select Windows Server 2012 R2 as a remote access server, and you are given a config file; now rename the extension to .ps1. When run in PowerShell, the script configures the local RAS server without any manual intervention.

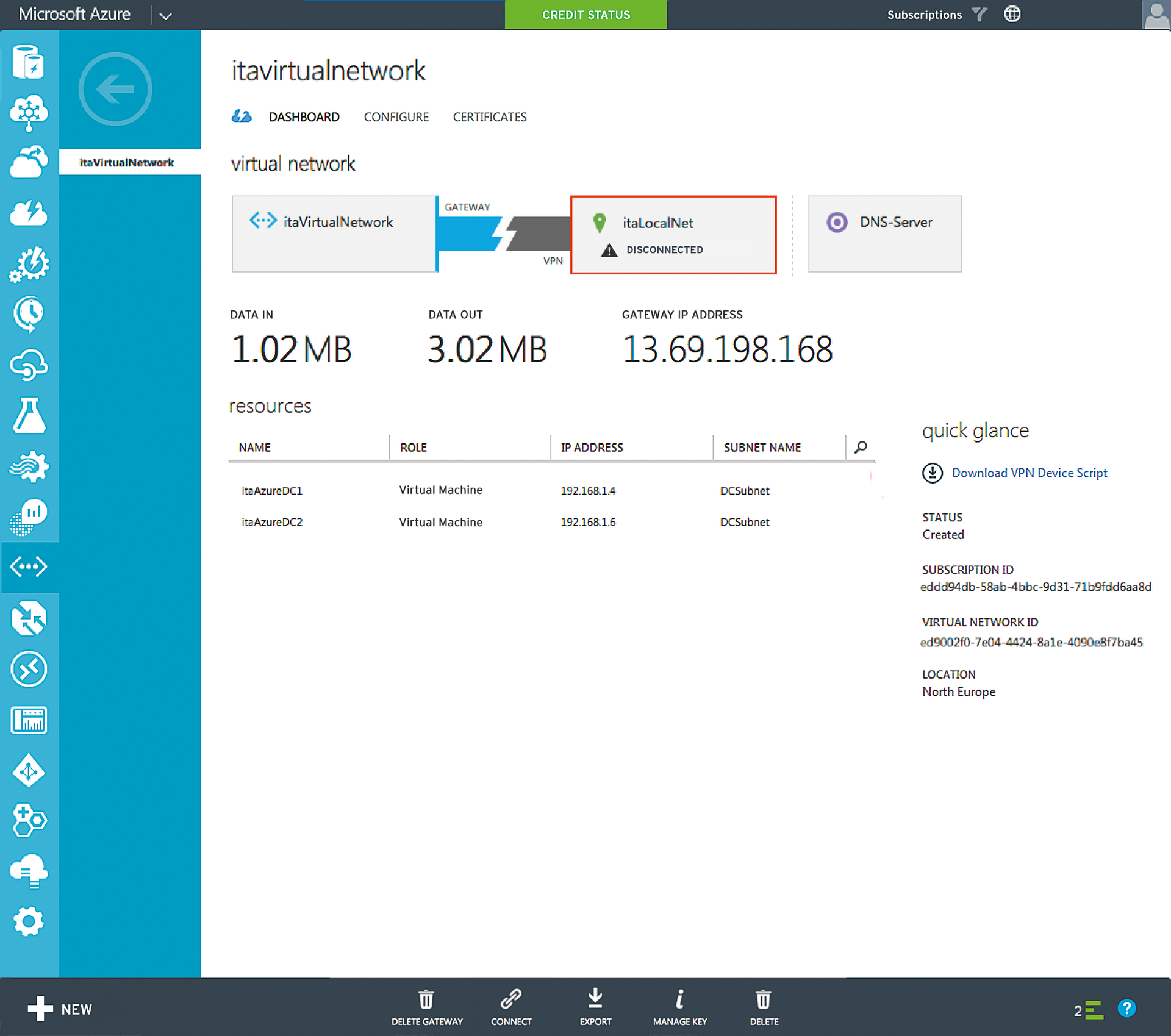

You can see the successfully established tunnel connection in the dashboard of the virtual network. If the remote access server is restarted, or is temporarily unavailable for some other reason, Azure attempts to restore the connection (Figure 4). For more details on the topic of networking, search the Azure document library.

Creating the Azure VM

Next, I will create the virtual machine for the first DC; use the classic portal for this purpose. First,you need to create the cloud service and the storage account for the VM. It is important that both follow a special notation: Additionally, the cloud service should be a public name that is unique on the Internet. The input is checked directly with a message telling you whether the names are valid.

Now you can create the virtual machine. Select the image Windows Server 2012 R2 with a size of A1, which is sufficient for a domain controller. The rest of the settings are self explanatory, except for one: Select the previously created subnet for the DCs – in this case, DCSubnet. This will ensure that the DHCP server is equipped with the necessary configuration and takes notice of the on-premises DNS server.

After the VM becomes available, open the dashboard for the VM. The dashboard gives you an overview of all the relevant data for the server. From here, you can also download an RDP file that takes you to the server via a Remote Desktop connection.

Preparing Active Directory

From an AD perspective, the new Azure site is just another site across a VPN connection. In the AD Sites and Services management console, create the subnet and the site based on the information from Azure. The name for the site is arbitrary. After the DCPROMO (when DC is promoted) process, the DC ends up on the right AD site thanks to its IP configuration.

Setting up a New Domain Controller

If you are logged on to the server via RDP, you should be able to ping the existing on-premises DC at the command prompt. In the settings of the network adapter, you will also see that the IP configuration was assigned via DHCP. In the status information, you will find the IP information for the virtual network, including the DNS server.

A computer receives a dynamically assigned address in Azure. A DC, on the other hand, requires a static IP address. To set up a static address in Azure PowerShell, use the Set-AzureStaticVNetIP cmdlet [5]. Before you assign the address, use the Test-AzureStaticV-NetIP cmdlet to see if the desired IP address is still available.

A newly created server in Azure has a drive "C" and a drive "D" out the box. The operating system is located on the C: drive and this is not a good place for the AD database. Neither is D: drive, which is temporary and not persistent. You thus need a new drive, which you specify in the DCPROMO process, for the folders for the AD database, logfiles, and SYSVOL. You can create the drive on the fly in Azure by selecting the Add command and then choosing the Empty data medium option from the dashboard. Moreover, be sure to select NONE for the cache settings. Caching may be useful in many cases, but not for AD databases. Now the preparatory work for promoting to a DC is complete. In addition to an empty disk, you can also assign a previously uploaded VHD file as a drive for the server to store an individual administrative toolset on the computers.

Depending on your configuration and the role you intend for your cloud resources, you might also want to set up a backup system. See the box titled "External Backup" for more on Azure's native backup service.

Learning More About Azure

Microsoft offers a free 30-day Azure subscription for your experiments, and many MSDN and Visual Studio subscriptions also include a month's credit for Azure [7]. As an MSDN customer, you will see this My Account option in the MSDN portal section. A new Azure subscription is linked with your MSDN account, and you can get started immediately. Also, I recommend the Microsoft Virtual Academy [8], which provides a wealth of training on the topics of Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) and Azure, or you could take a look at Channel 9 [9], where Microsoft regularly publishes keynotes from international conferences.

Conclusions

IaaS services provide much more than just virtual hardware replacement. The mere fact that data and infrastructure components are no longer stored exclusively at the local data center, but redundantly and far outside of the local campus, is something that calms the admin's nerves. This is particularly true of DCs and security vaults, and it holds a special charm for these valuable technologies. However, Azure can do much more than what I presented in this article. The Azure document library provides a wealth of information on a variety of topics. Make sure, though, that you check when the article was published. Azure is evolving rapidly, and you'll find that some articles are already out of date.